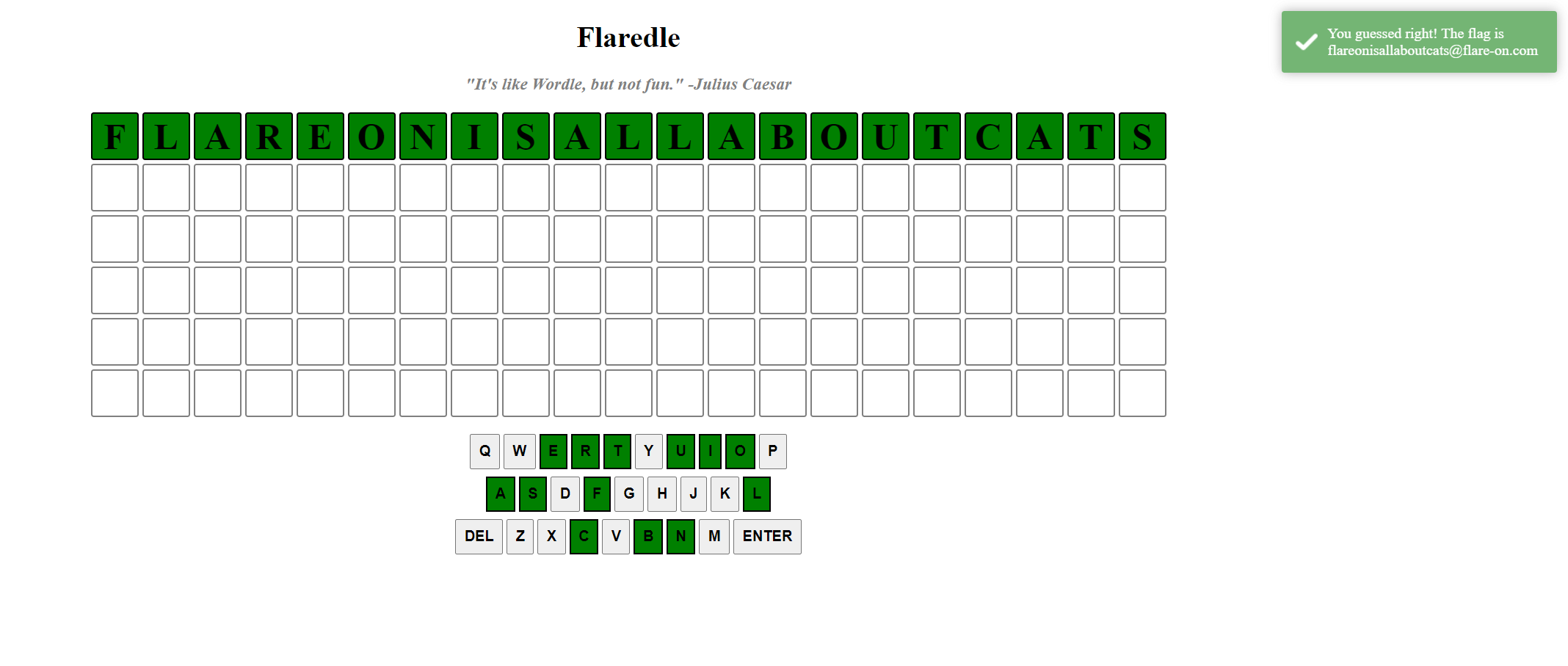

01 - flaredle 🔗

Welcome to Flare-On 9!

You probably won’t win. Maybe you’re like us and spent the year playing Wordle. We made our own version that is too hard to beat without cheating.

Play it live at: http://flare-on.com/flaredle/

Files :

index.htmlscript.jsstyle.cssword.js

This challenge is a custom version of Wordle, the hit game of the Covid-19 lockdown.

This version uses 21-characters long words…chances are that finding the right word will give us the flag!

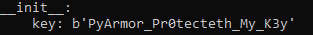

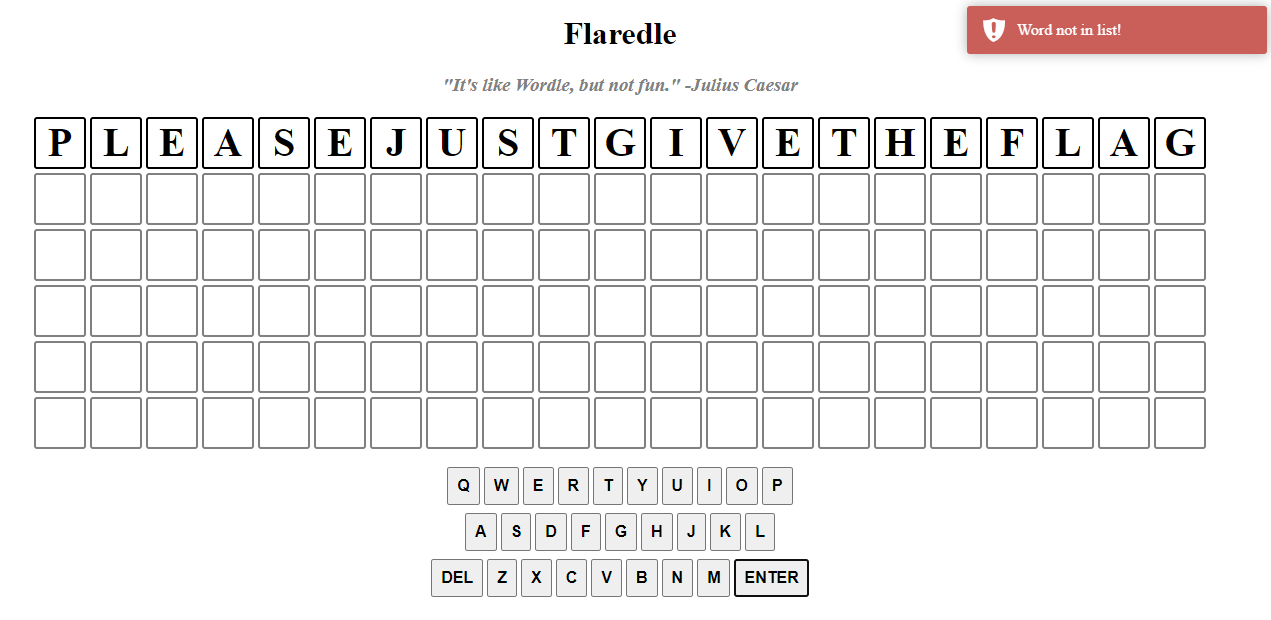

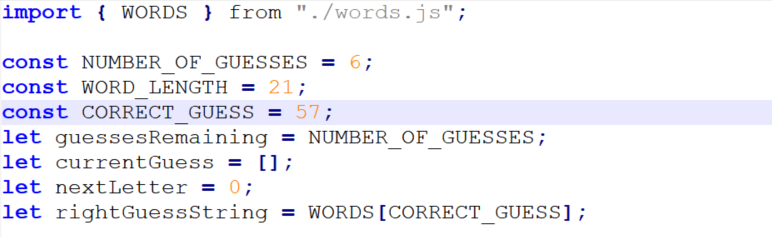

So let’s start by analyzing script.js :

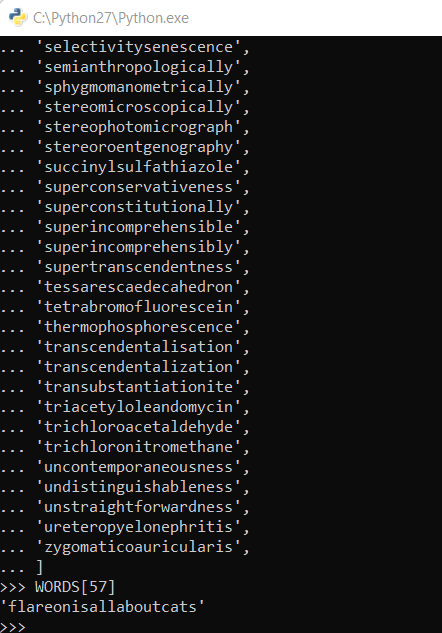

We can see that the dictionary is in the words.js file, and that the correct one is the one in 58th position.

To get this word, we copy-paste the word list in a Python interpreter and go fetch WORDS[57] ourselves!

The correct word seems to be flareonisallaboutcats! Let’s try to input it in the game now…

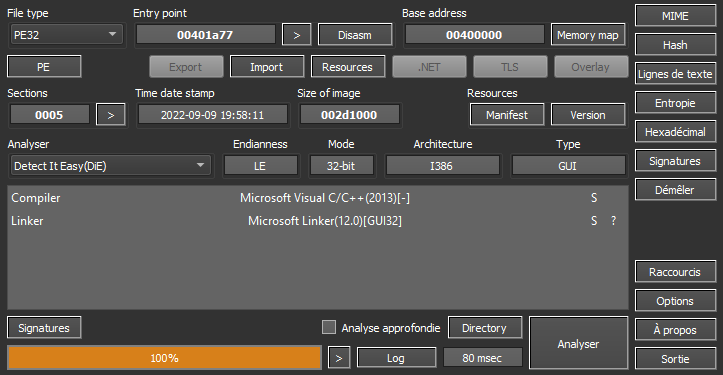

02 - Pixel Poker 🔗

I said you wouldn’t win that last one. I lied. The last challenge was basically a captcha. Now the real work begins. Shall we play another game?

Files:

PixelPoker.exereadme.txt

Here’s the contents of readme.txt:

Welcome to PixelPoker ^_^, the pixel game that's sweeping the nation!

Your goal is simple: find the correct pixel and click it

Good luck!

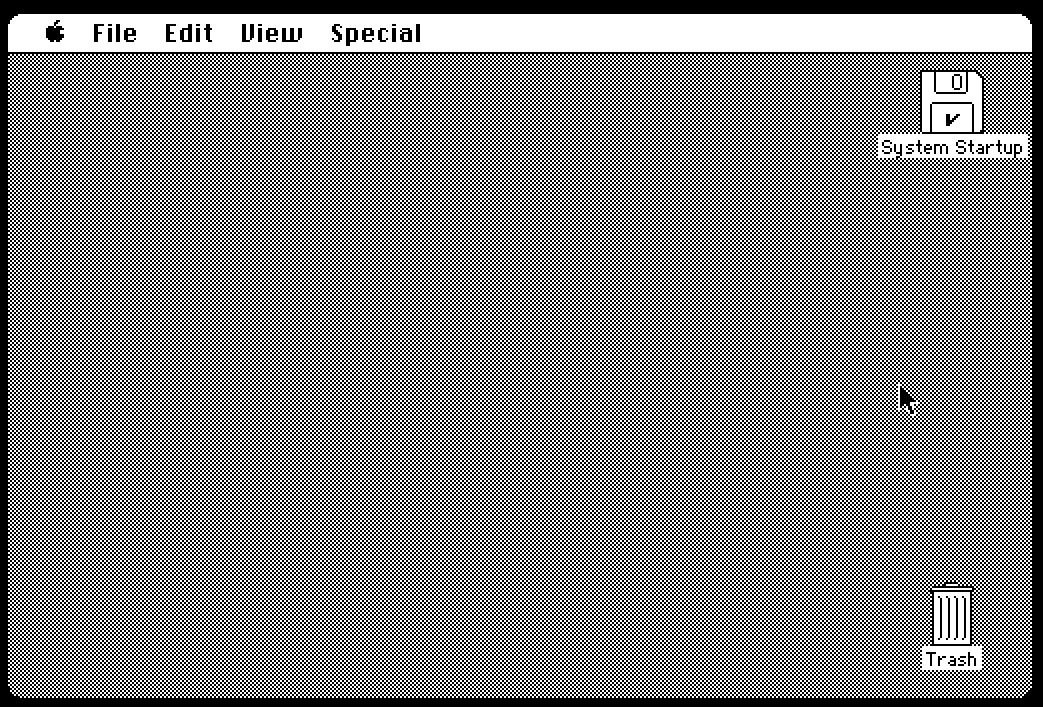

Running the provided executable opens up a window with a bunch of random noise. Our cursor position is indicated in the window title.

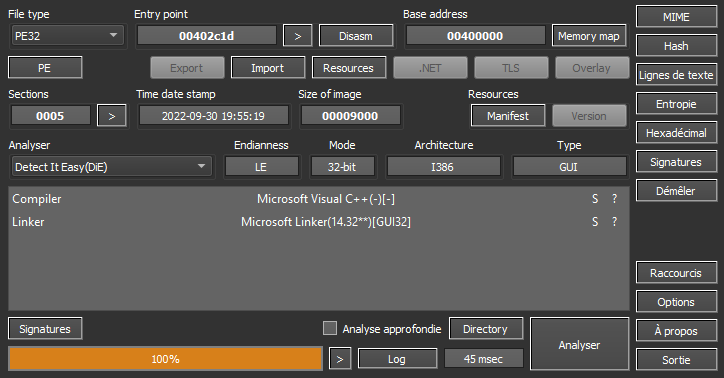

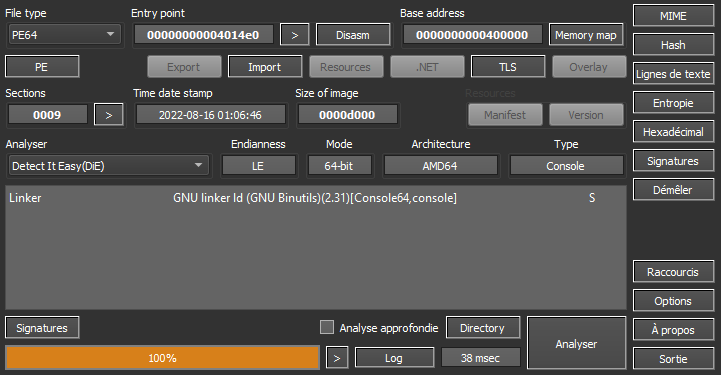

Let’s run the executable through Detect-it-Easy to have a first idea of what it is.

Well, a 32 bit GUI app compiled with MSVC. Nothing too original just yet. Let’s open it in IDA. We can quickly find the function responsible for handling window messages:

We can see some code responsible for updating the window title (handling message 512, WM_MOUSEMOVE). Then, if the user didn’t click, the function exits prematurely (513 is WM_LBUTTONDOWN). A complete list of Windows message can be found on the WineHQ wiki.

We had to find the pixel to click on, and brute-force wasn’t an option because we only had 10 tries before the app stops and shows a game-over image.

We can see that the x position of the click is checked against dword_412004 % dword_413280. The first operand is static (0x52414C46) and the second one is used in the game-over clause to display the picture, as the fourth argument. Let’s remind ourselves of the BitBlt method:

BOOL BitBlt(

[in] HDC hdc,

[in] int x,

[in] int y,

[in] int cx,

[in] int cy,

[in] HDC hdcSrc,

[in] int x1,

[in] int y1,

[in] DWORD rop

);

The fourth argument is cx: (MSDN docs)

[in] cxThe width, in logical units, of the source and destination rectangles.

We can infer that the width in pixels of the game-over image is the same as the window, so 741.

The same can be applied to the second check: the y position is checked against dword_412008 % cy. The first operand has a fixed value of 0x6E4F2D45, and cy is 641 in our case.

By doing the math ourselves, we find:

x = 0x52414C46 % 741 = 95y = 0x6E4F2D45 % 641 = 313

After clicking on the pixel at (95, 313), we get the flag.

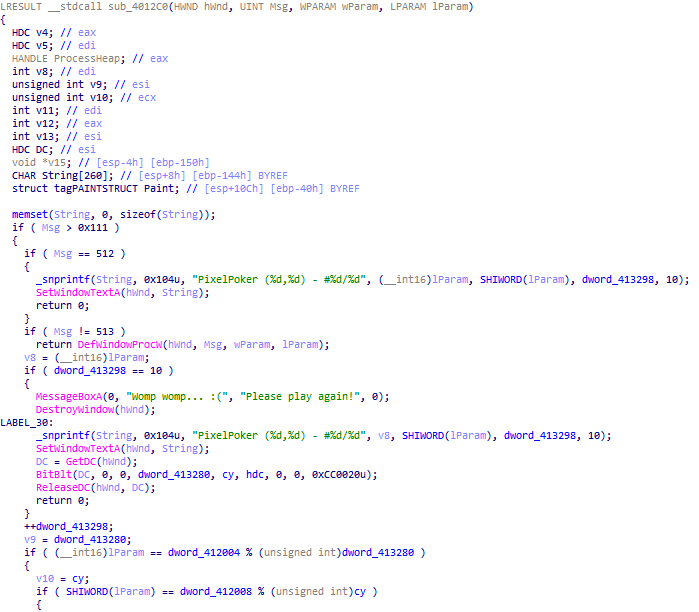

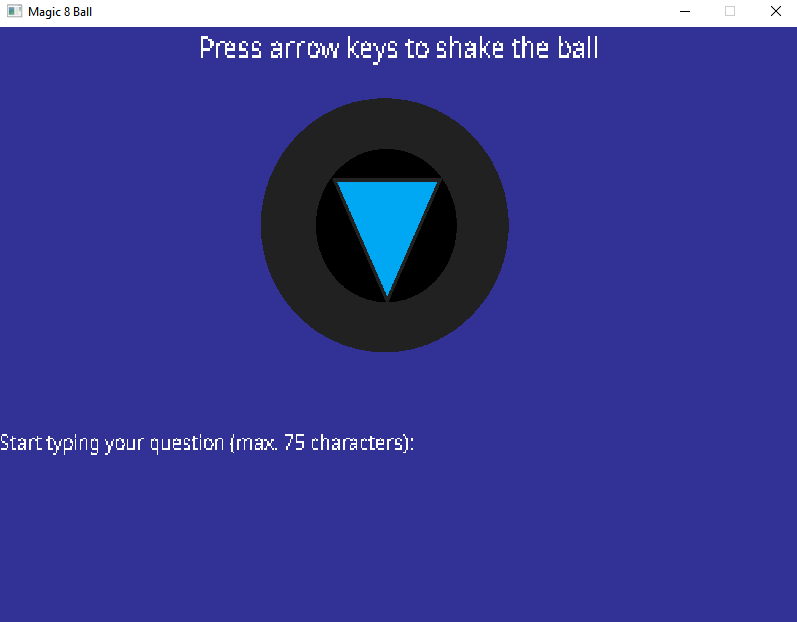

03 - Magic 8 Ball 🔗

You got a question? Ask the 8 ball!

Files:

assets/ball_paint.png- Fonts

- DLLs

Magic8Ball.exe

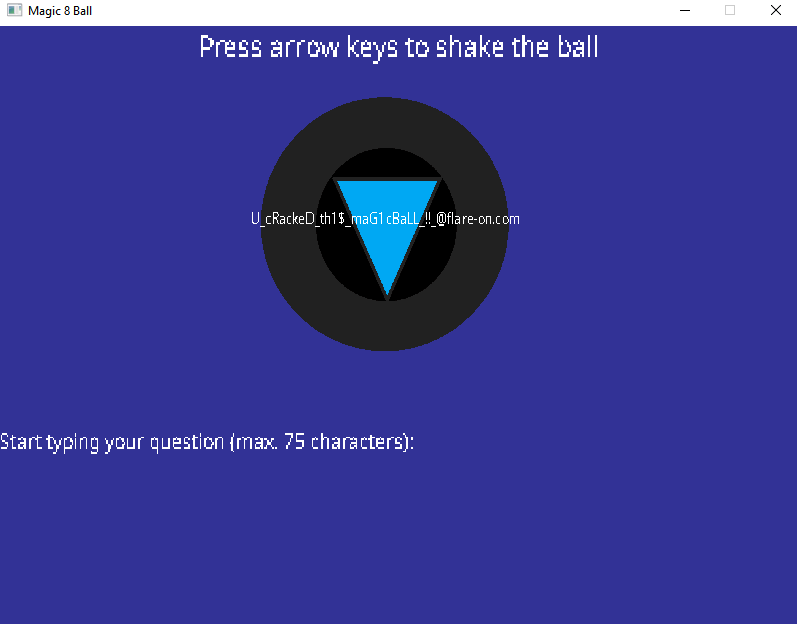

Let’s run the program to see what it does!

We can ask a question to the magic 8 ball by typing it in the window, and then shake the ball by using the arrow keys. Finally, we can press the Enter key to get an answer.

Once again, let’s use Detect-it-Easy to see what the executable is made of.

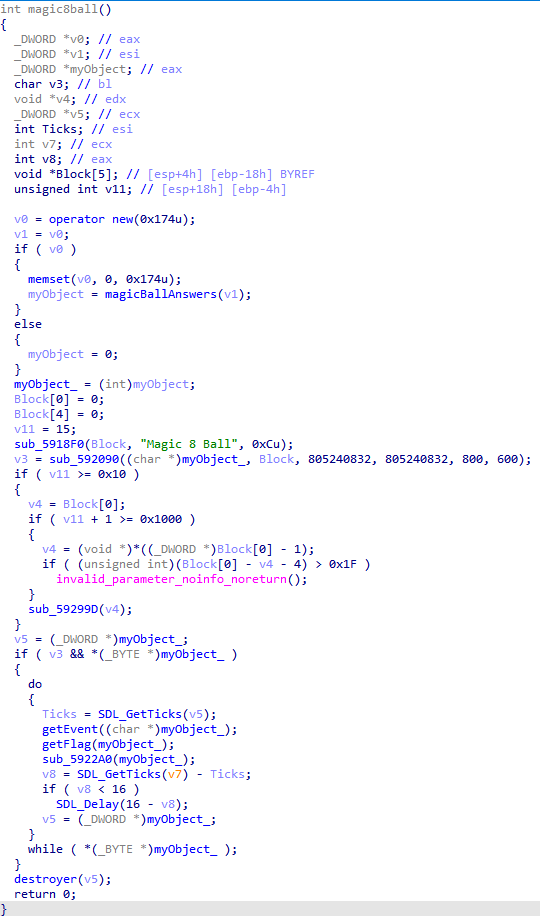

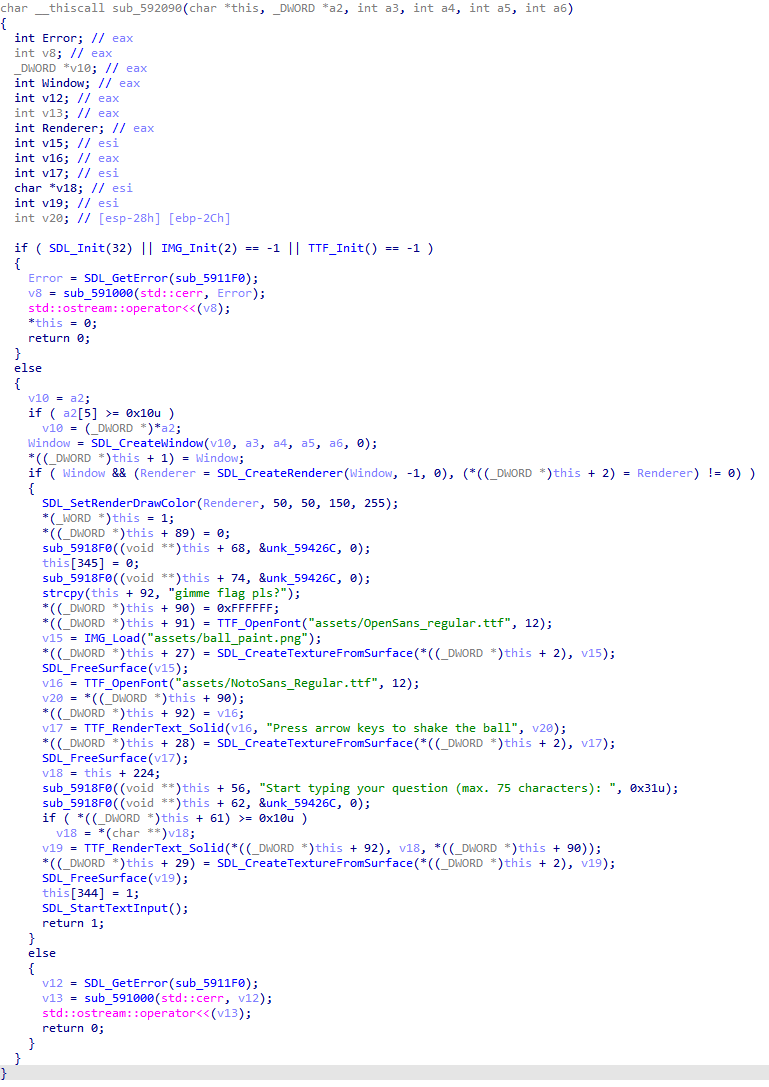

Another 32 bit GUI app built with MSVC! When we opened the PE in IDA, we quickly identified the main part:

The constructor initialized the object’s members before doing anything else. We can see all the possible answers, and other values we don’t know the use of yet.

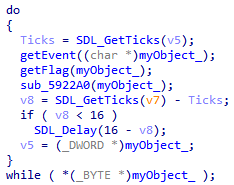

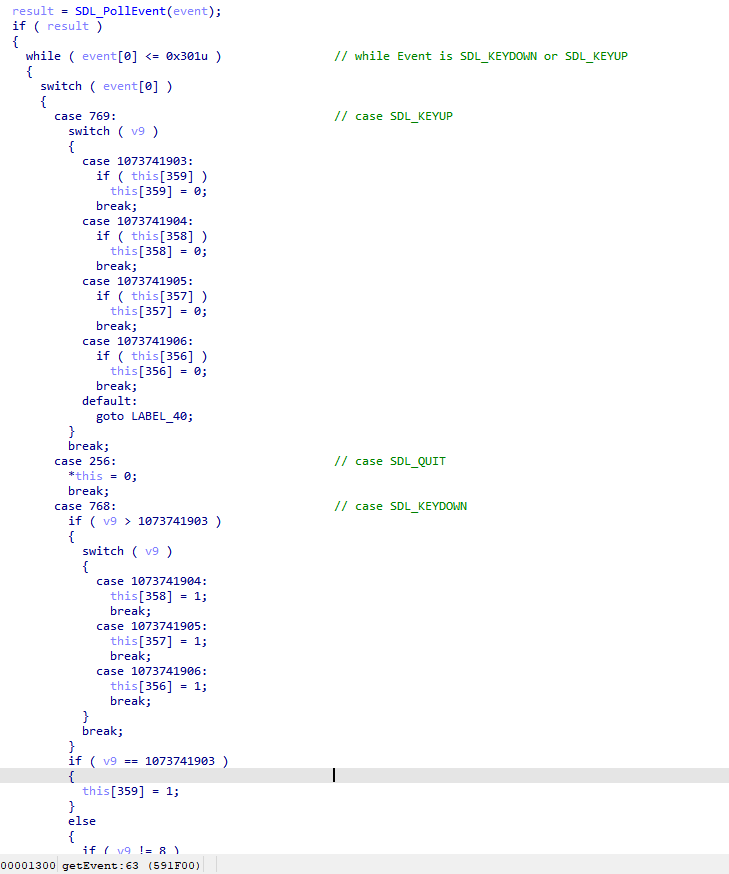

Once the object initialized, the program entered in a loop to filter the different events:

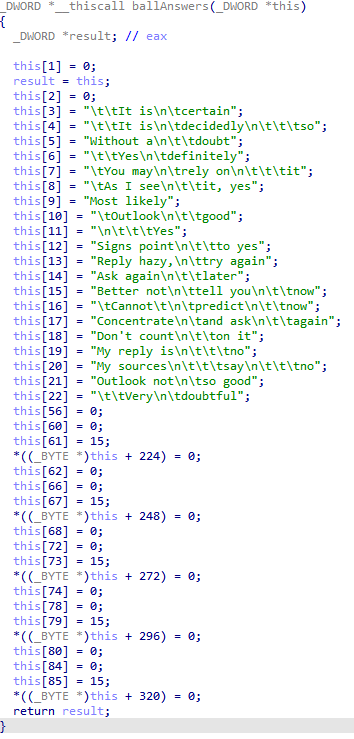

We didn’t dig too much in getEvent:

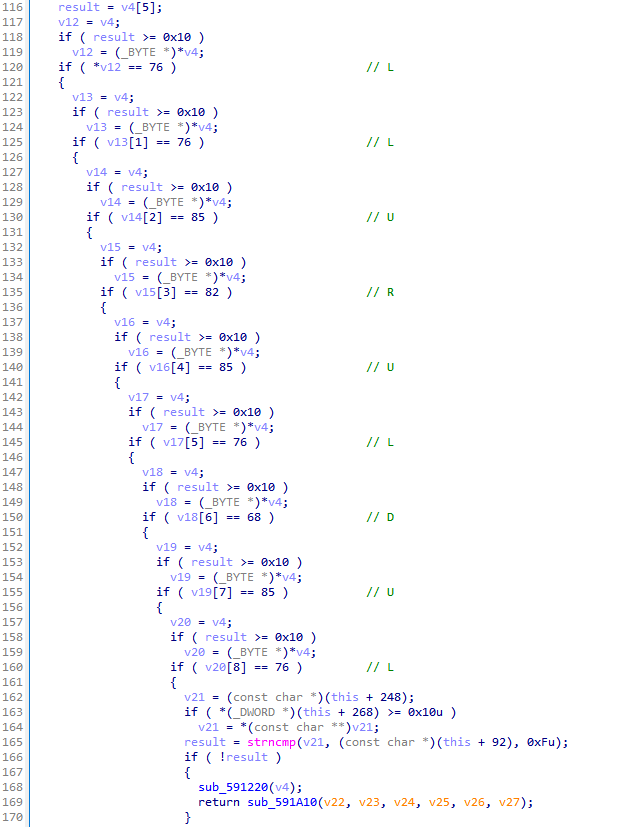

The important stuff was in getFlag…

Magic8Ball checked if the last pressed keys where equal to the characters “LLURULDUL”, “L” for Left, “R” for “Right”, etc… Then, it compared our input with a string stored in the object, so we went back to the last manipulation of myObject_: sub_592090

It copied “gimme flag pls?" in this + 92. So we tried to enter this question in the box, and pressed the right arrow key combination:

04 - darn_mice 🔗

“If it crashes its user error.” -Flare Team

Files :

darn_mice.exe

darn_mice.exe is an x86 executable. When opened into IDA, the main function is :

int __cdecl sub_401000(char *Str)

{

void (__cdecl *v2)(_DWORD); // eax

size_t v3; // [esp+4h] [ebp-30h]

unsigned int i; // [esp+8h] [ebp-2Ch]

BYTE v5[36]; // [esp+Ch] [ebp-28h] BYREF

qmemcpy(v5, "P^^", 3);

v5[3] = 0xA3;

v5[4] = 0x4F;

v5[5] = 0x5B;

v5[6] = 0x51;

v5[7] = 0x5E;

v5[8] = 0x5E;

v5[9] = 0x97;

v5[10] = 0xA3;

v5[11] = 0x80;

v5[12] = 0x90;

v5[13] = 0xA3;

v5[14] = 0x80;

v5[15] = 0x90;

v5[16] = 0xA3;

v5[17] = 0x80;

v5[18] = 0x90;

v5[19] = 0xA3;

v5[20] = 0x80;

v5[21] = 0x90;

v5[22] = 0xA3;

v5[23] = 0x80;

v5[24] = 0x90;

v5[25] = 0xA3;

v5[26] = 0x80;

v5[27] = 0x90;

v5[28] = 0xA3;

v5[29] = 0x80;

v5[30] = 0x90;

v5[31] = 0xA2;

v5[32] = 0xA3;

v5[33] = 0x6B;

v5[34] = 0x7F;

v5[35] = 0;

printf("On your plate, you see four olives.\n");

v3 = strlen(Str);

if ( !v3 || v3 > 35 )

return printf("No, nevermind.\n");

printf("You leave the room, and a mouse EATS one!\n");

for (i = 0; i < 36 && v5[i] && Str[i]; ++i )

{

v2 = (void (__cdecl *)(_DWORD))VirtualAlloc(NULL, 0x1000u, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

*(_BYTE *)v2 = Str[i] + v5[i];

v2(v2);

printf("Nibble...\n");

}

printf("When you return, you only: %s\n", Str);

mw_encrypt((int)byte_419000, dword_419030, (PUCHAR)Str, pbSalt, (int)byte_419000, dword_419030);

return printf("%s\n", byte_419000);

}

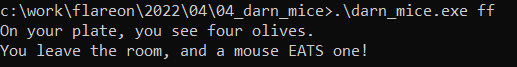

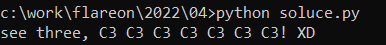

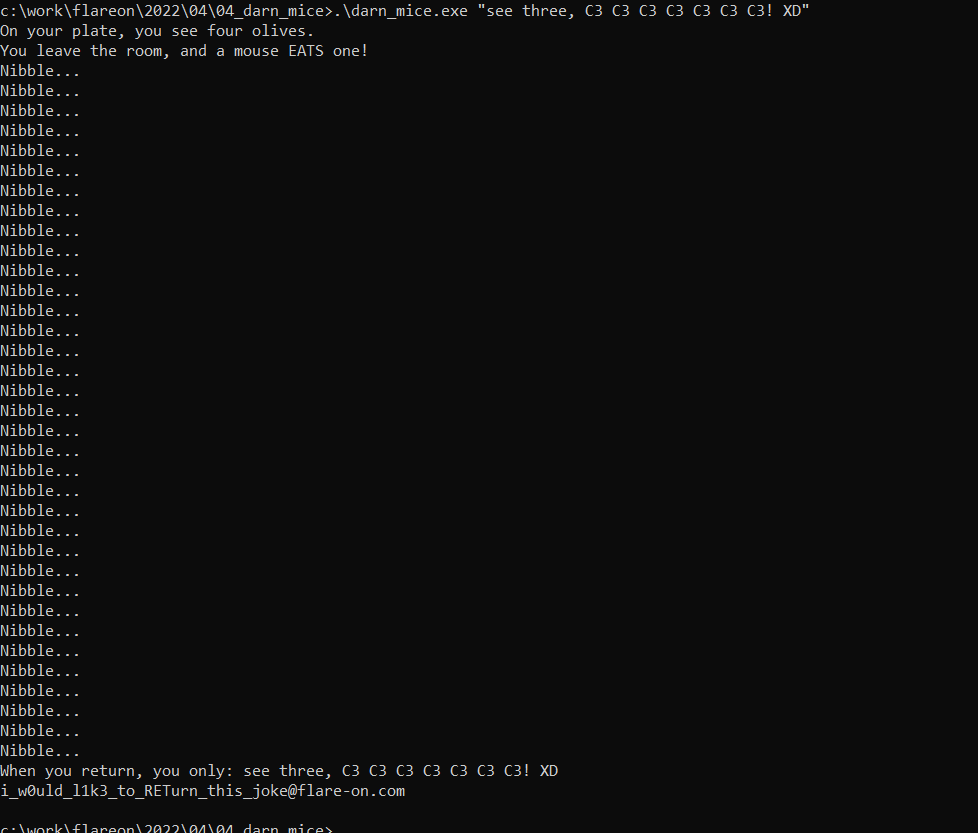

We can see the program checks for the existence of a command-line argument, and that the length of this parameter is 35 or less. Let’s give it an argument :

The program seems to crash, as noted by the author of the challenge in the introduction…

It seems that the “Nibble” is never printed on my console, so the crash happens before… and oh what is this?

v2 = (void (__cdecl *)(_DWORD))VirtualAlloc(NULL, 0x1000u, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

*(_BYTE *)v2 = Str[i] + v5[i];

v2(v2);

The code tries to jump inside a memory region with the executable flag, whose first byte is the result of the addition of a static variable and the input of the user…

And it loops over the 35 bytes of the static array.

Ok, we have to find an x86 opcode, with a one-byte size that can be called without crashing the program. The only one is the RET instruction, coded 0xC3.

Every byte from the static array added with user input must be equal to 0xC3 :

v5[i] + Str[i] == 0xc3

Let’s make a little python script :

static = [0x50,0x5e,0x5e,0xA3,0x4F,0x5B,0x51,0x5E,0x5E,0x97,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA3,0x80,0x90,0xA2,0xA3,0x6B,0x7F]

print("".join([chr(0xc3 - x) for x in static]))

And magic happens:

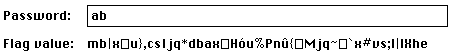

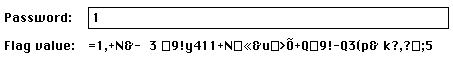

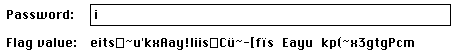

So let’s try our passphrase :

05 - T8 🔗

FLARE FACT #823: Studies show that C++ Reversers have fewer friends on average than normal people do. That’s why you’re here, reversing this, instead of with them, because they don’t exist.

We’ve found an unknown executable on one of our hosts. The file has been there for a while, but our networking logs only show suspicious traffic on one day. Can you tell us what happened?

Files:

t8.exetraffic.pcapng

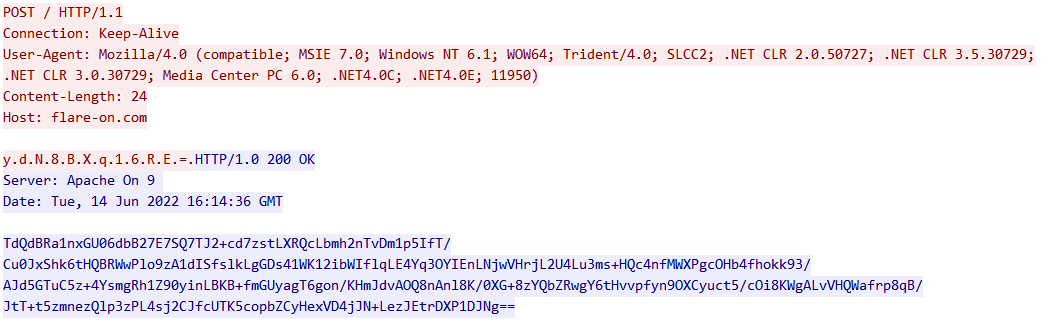

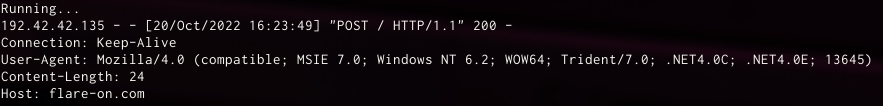

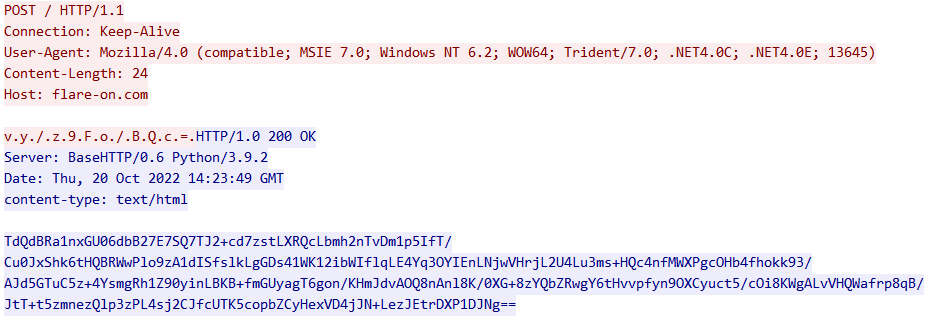

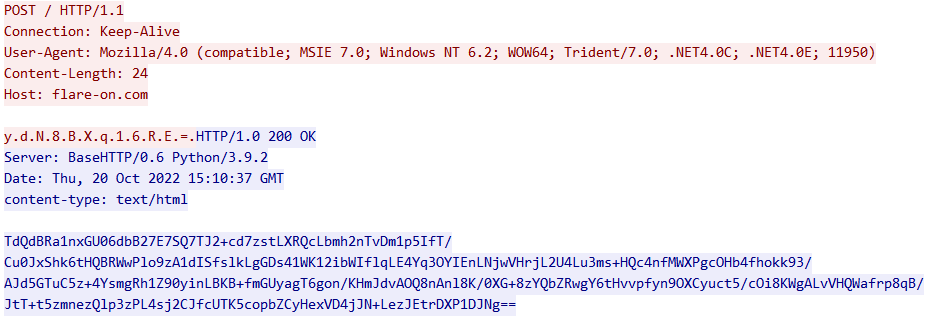

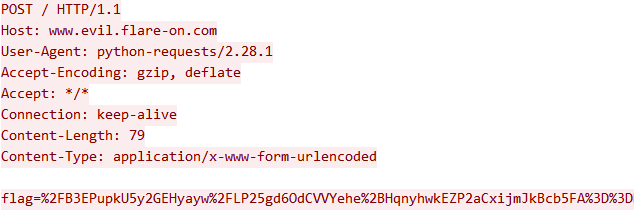

When we first opened the PCAP file, we instantly understood that t8.exe was sending an UTF16-encoded base64 key to flare-on.com, and received a base64 message in return.

t8.exe was a 32 bits C++ console program. In order to reproduce what happened in the pcap, we made a little Python Web server that responds the same base64 message and modified the Windows hosts file to redirect flare-on.com to our server:

from http.server import HTTPServer, BaseHTTPRequestHandler

class CustomHandler(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_POST(self):

self.send_response(200)

self.wfile.write(

b'TdQdBRa1nxGU06dbB27E7SQ7TJ2+cd7zstLXRQcLbmh2nTvDm1p5IfT/Cu0JxShk6tHQBRWwPlo9zA1dISfslkLgGDs41WK12ibWIflqLE4Yq3OYIEnLNjwVHrjL2U4Lu3ms+HQc4nfMWXPgcOHb4fhokk93/AJd5GTuC5z+4YsmgRh1Z90yinLBKB+fmGUyagT6gon/KHmJdvAOQ8nAnl8K/0XG+8zYQbZRwgY6tHvvpfyn9OXCyuct5/cOi8KWgALvVHQWafrp8qB/JtT+t5zmnezQlp3zPL4sj2CJfcUTK5copbZCyHexVD4jJN+LezJEtrDXP1DJNg=='

)

print(self.headers)

def main():

srv = HTTPServer(('',80), CustomHandler)

print('Running...')

srv.serve_forever()

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

exit()

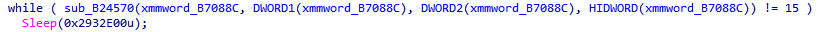

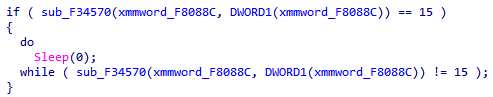

But nothing happened… At all… So we checked the code:

That’s a long sleep! Let’s edit the sleep time to “0”.

Because it was still looping forever after patching the sleep, we just took off the condition…

Then, we started the patched program, and finally we get something!

Here is some information we had to keep in mind: the integer at the end of the User-Agent changed, as well as the base64 key.

So we had to dig a little more in this PE.

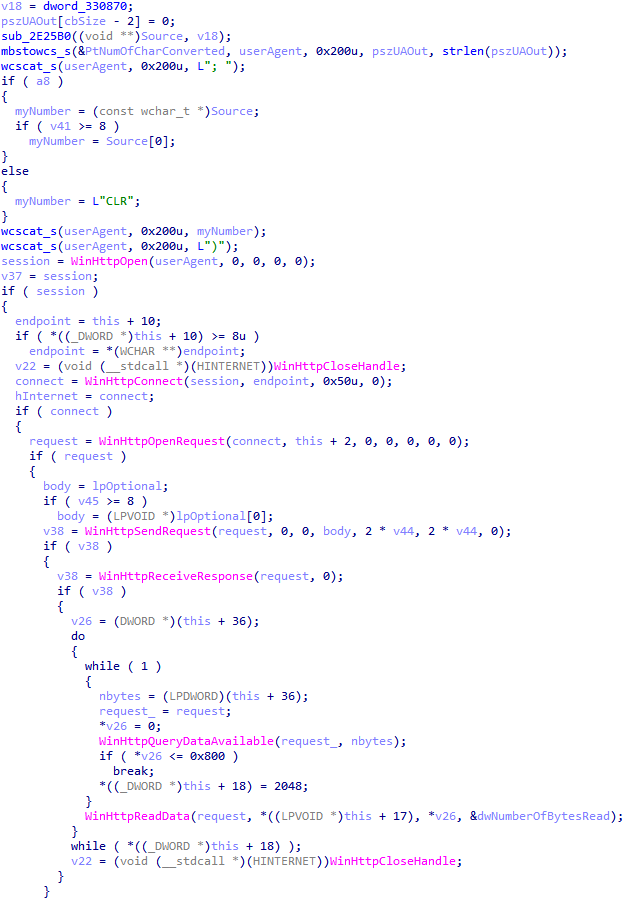

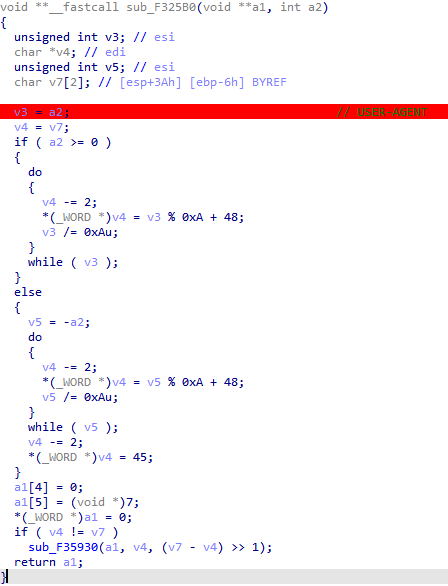

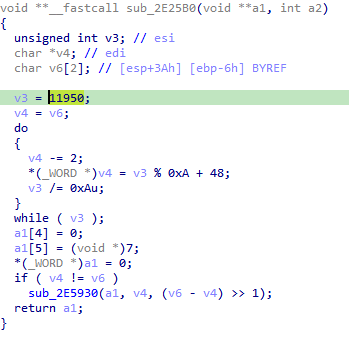

By going through the code, we easily spotted the place where it sends its HTTP request:

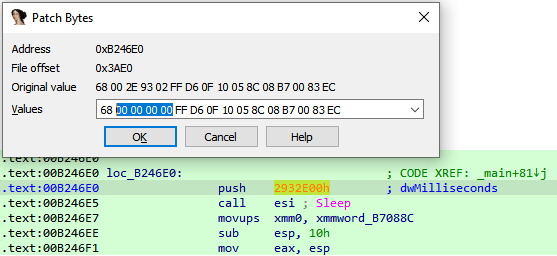

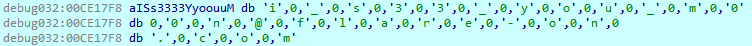

It was also the place where it adds the random number (myNumber) to the User-Agent header. The function sub_2E25B0 was the last one to handle this number before concatenating it. It was actually converting it into a string:

We simply patched this function to hardcode the value 11950 in v3, as seen in the original PCAP:

Then we executed the PE again and surprise…

It changed the integer in the header, but we also got the same base64-encoded key from the original PCAP! But why? Because lost into wild, t8.exe encrypts the string “ahoy” with the random integer (for some reason, it does it on 64bits for every single character).

Because of our incredible laziness, we decided to put a breakpoint at the output of the HTTP response decryption:

i_s33_you_m00n@flare-on.com

We made it!

06 - à la mode 🔗

FLARE FACT #824: Disregard flare fact #823 if you are a .NET Reverser too.

We will now reward your fantastic effort with a small binary challenge. You’ve earned it kid!

Files :

HowDoesThisWork.dll

As expected by the introduction the dll is a .Net assembly :

> file HowDoesThisWork.dll

HowDoesThisWork.dll: PE32 executable (DLL) (GUI) Intel 80386 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS Windows

There was another file with the challenge, which seems to be a dump of an internal chat with the IR team:

[FLARE Team] Hey IR Team, it looks like this sample has some other binary that might

interact with it, do you have any other files that might be of help.

[IR Team] Nope, sorry this is all we got from the client, let us know what you got.

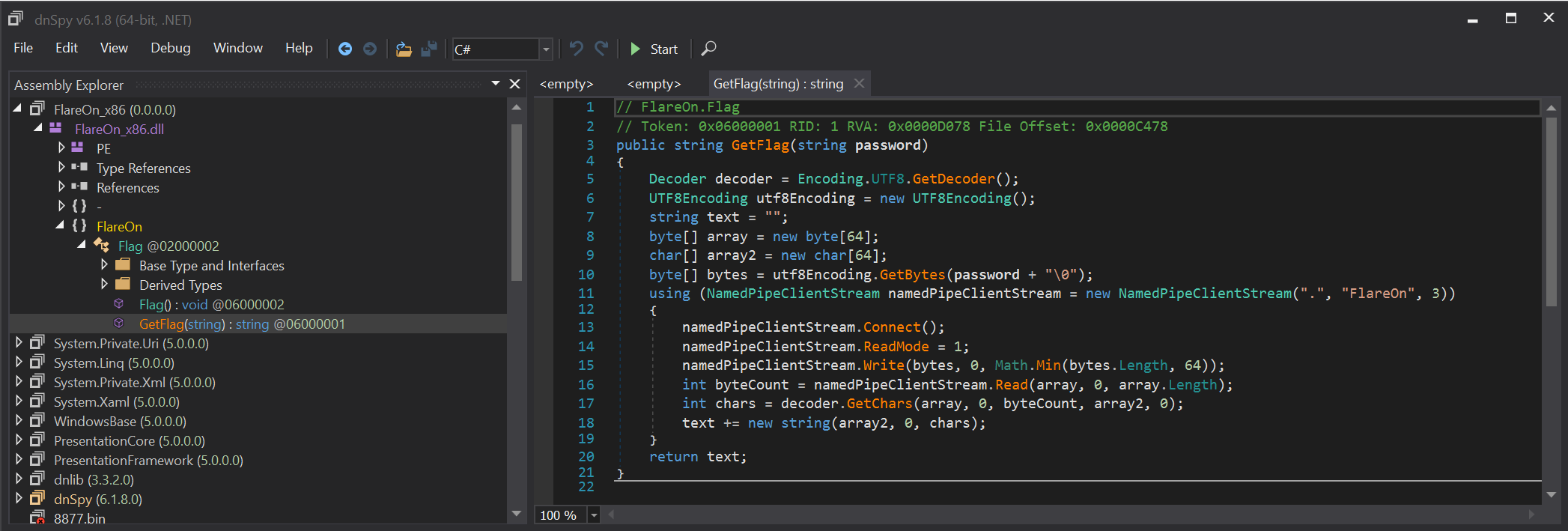

Let’s use the best .NET reverse tool : dnSpy

The code is pretty simple, only one function named GetFlag tries to connect to a named pipe named \\.\Flareon, sends a password, and expects the flag as a return.

But who is on the other side of the named pipe?

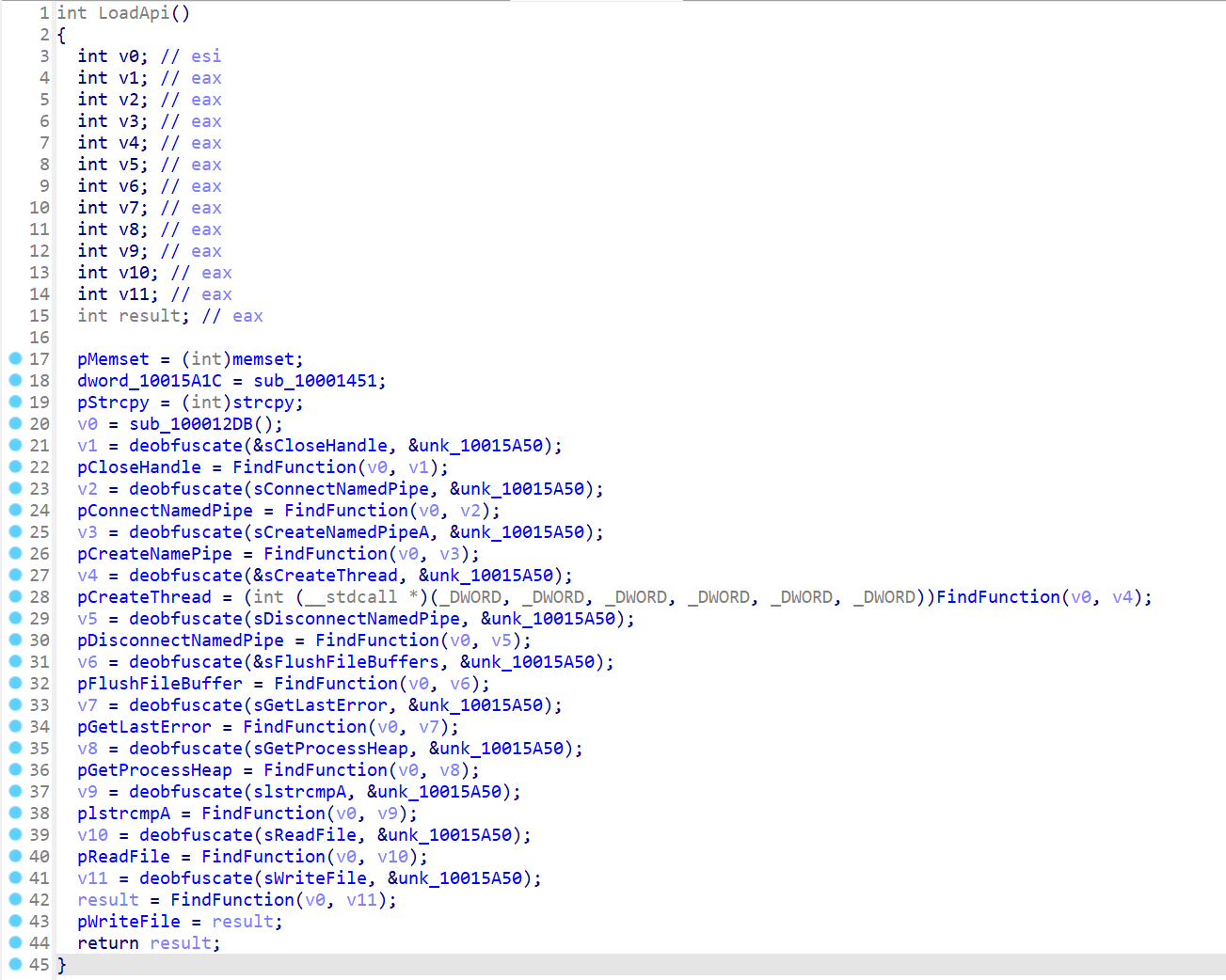

Because this DLL is the only binary delivered by the IR team (see note), we thought that the binary was self-sufficient. So we will open it now with a low-level disassembler, like IDA :

We analyzed the DLL entry point and saw normal C runtime (CRT) stuff. The DLL mixes native and managed code, it’s not a pure managed assembly. It reminds me of a project named DllExport, which exports managed functions to a native application.

By analyzing functions called from the dllmain_dispatch function, we observed a particular function called LoadApi():

This function dynamically loads functions from obfuscated names. The function pointers are stored in global variables. We can see the program loading methods related to named pipe usage, which tells us we are on the right track:

CreateNamedPipeAConnectNamedPipe

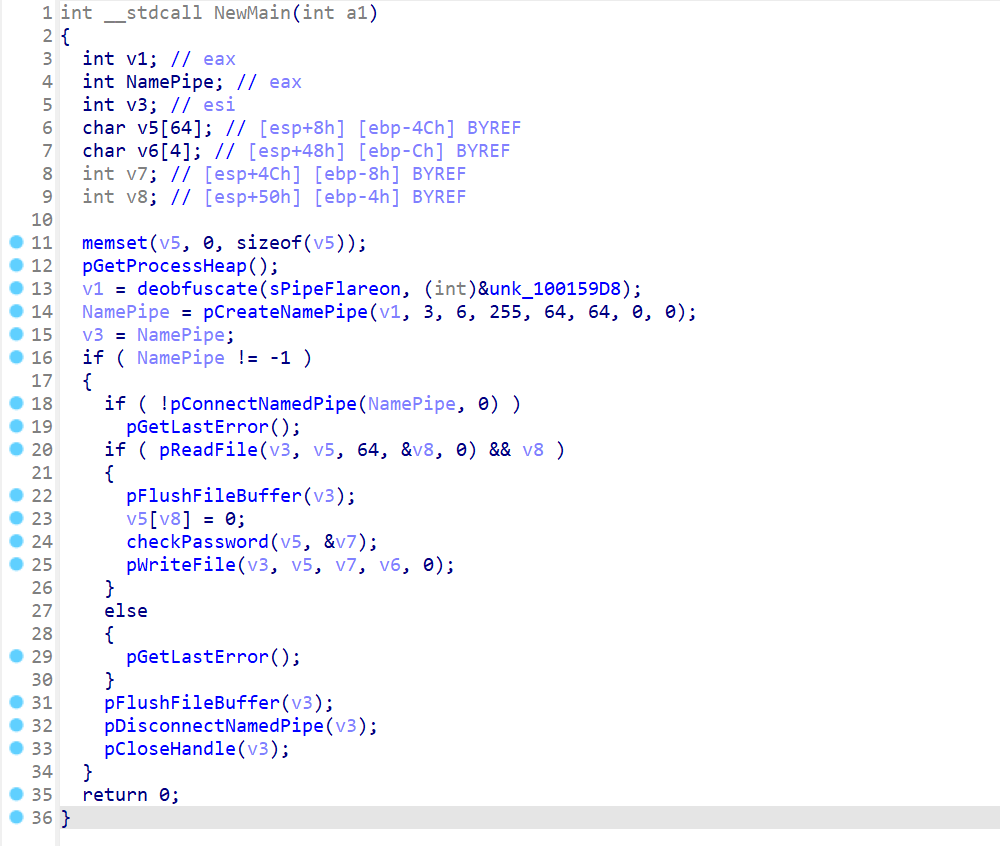

So by searching cross-references to these global variables, we found where the pipe methods are used.

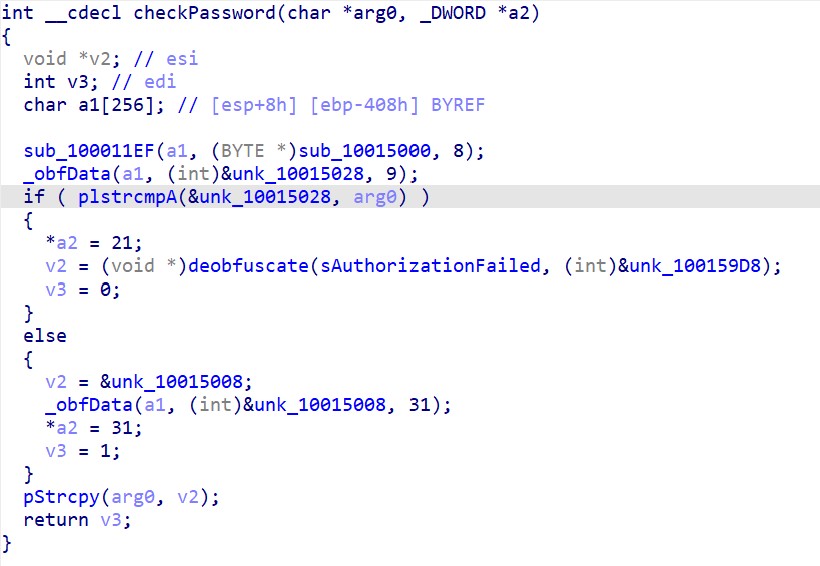

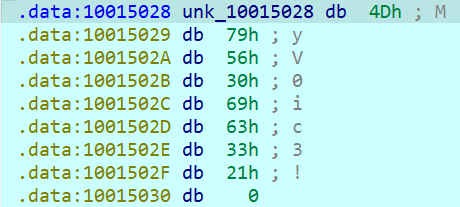

And finally where the password is checked :

The check is a comparison with static obfuscated data. Then the flag is deobfuscated from static data as well.

There are two ways we can get the flag now:

- Continue in static analysis and understand and reimplement the obfuscation algorithm

- Use dynamic analysis and break when the password is deobfuscated

We chose the second one!!!

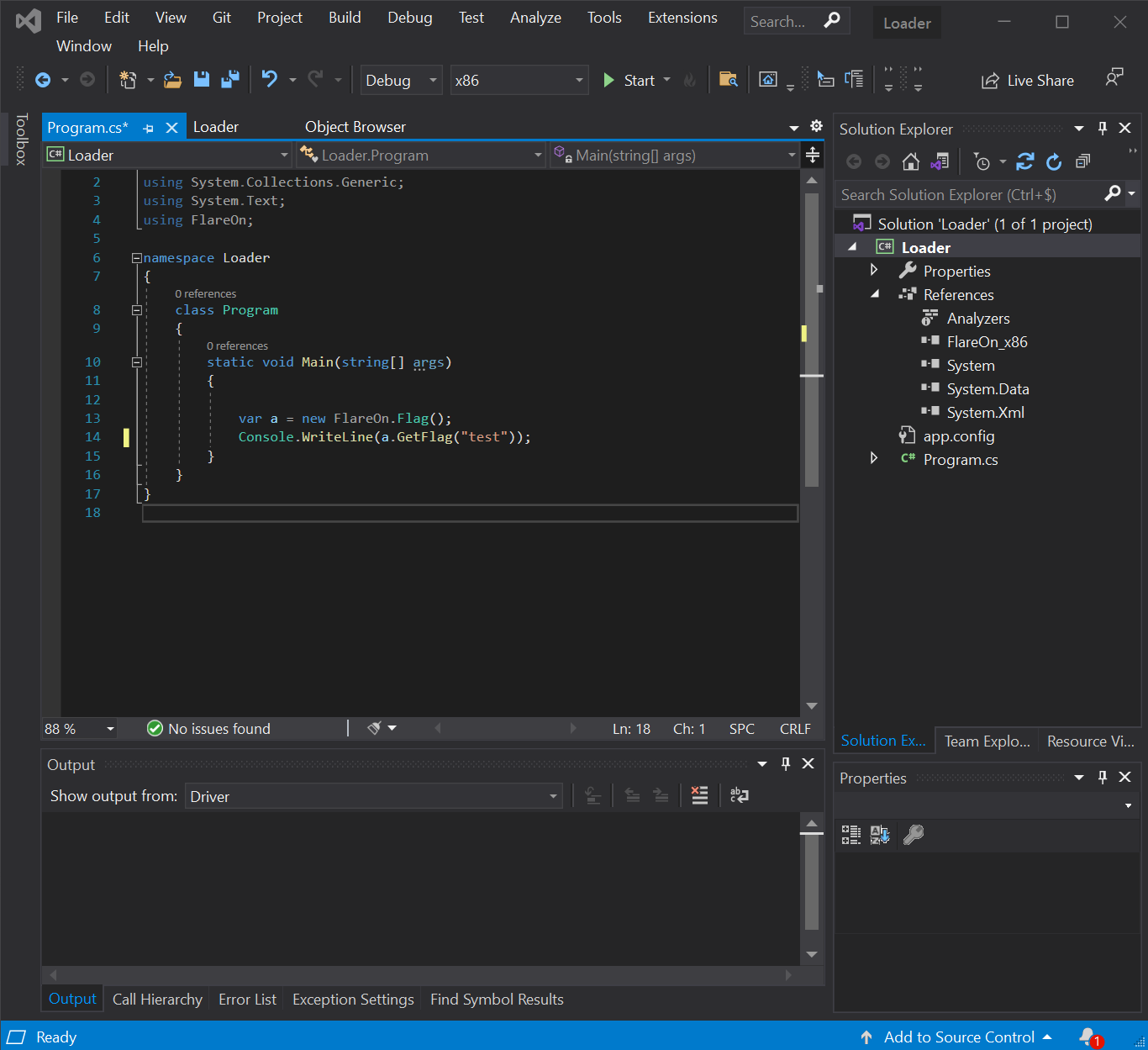

When we loaded the assembly into dnSpy we found the original name: FlareOn_x86. By renaming the assembly FlareOn_x86.dll we can create a new .NET project, with FlareOn_x86.dll in references, and call the GetFlag API ourselves.

When we launched the exe, we have the expected “Authorization Failed” string as seen in the checkPassword function.

Let’s relaunch the binary in debugging with a breakpoint at the appropriate place :

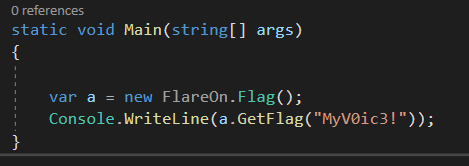

Bingo the password is MyV0ic3! !!!

Now we can relaunch our program with the right password!

07 - anode 🔗

You’ve made it so far! I can’t believe it! And so many people are ahead of you!

Files :

anode.exe

The binary seems to have the same icon as NodeJS, the famous JavaScript engine!

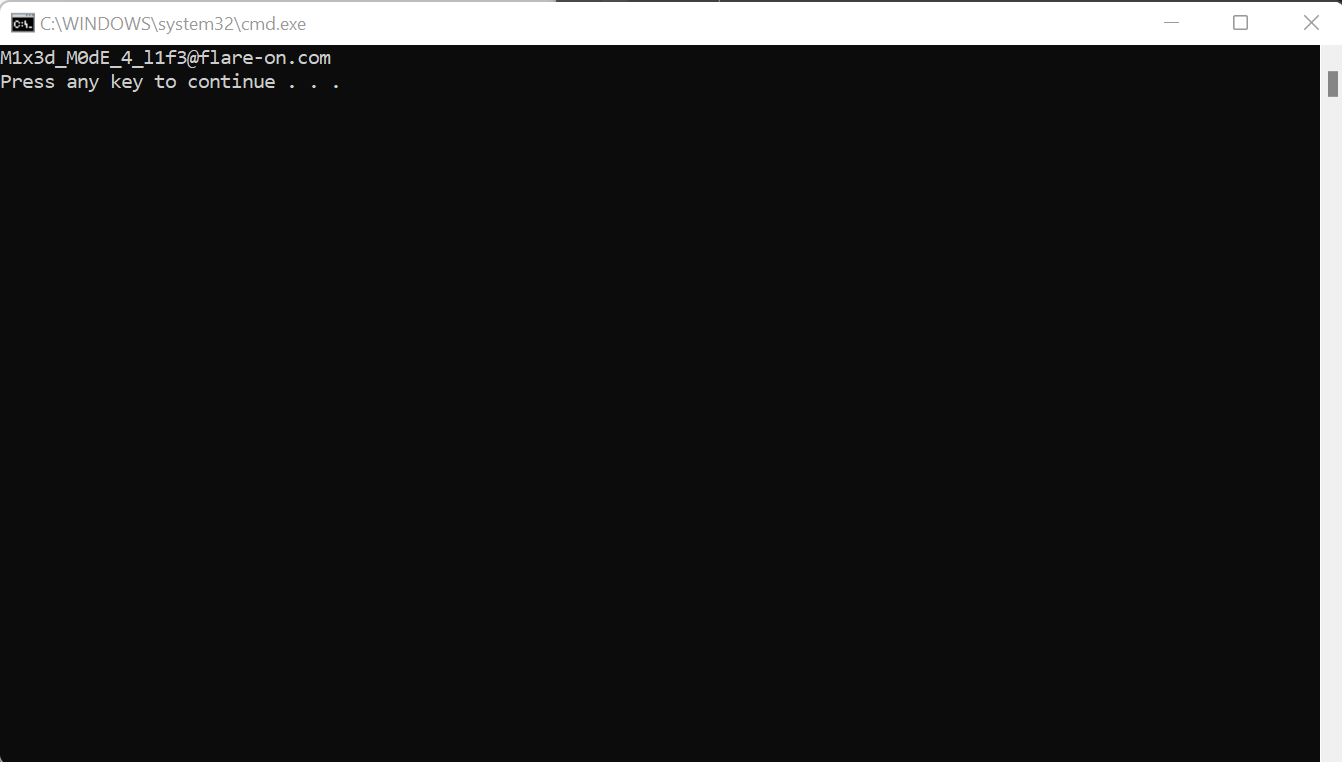

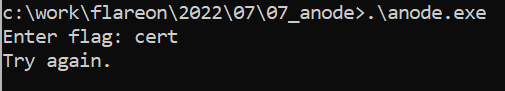

Before digging into it, we tried it :

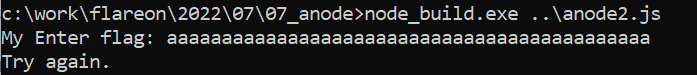

It’s not a normal node.exe, even if we pass a javascript as a parameter, the executable ask for a flag.

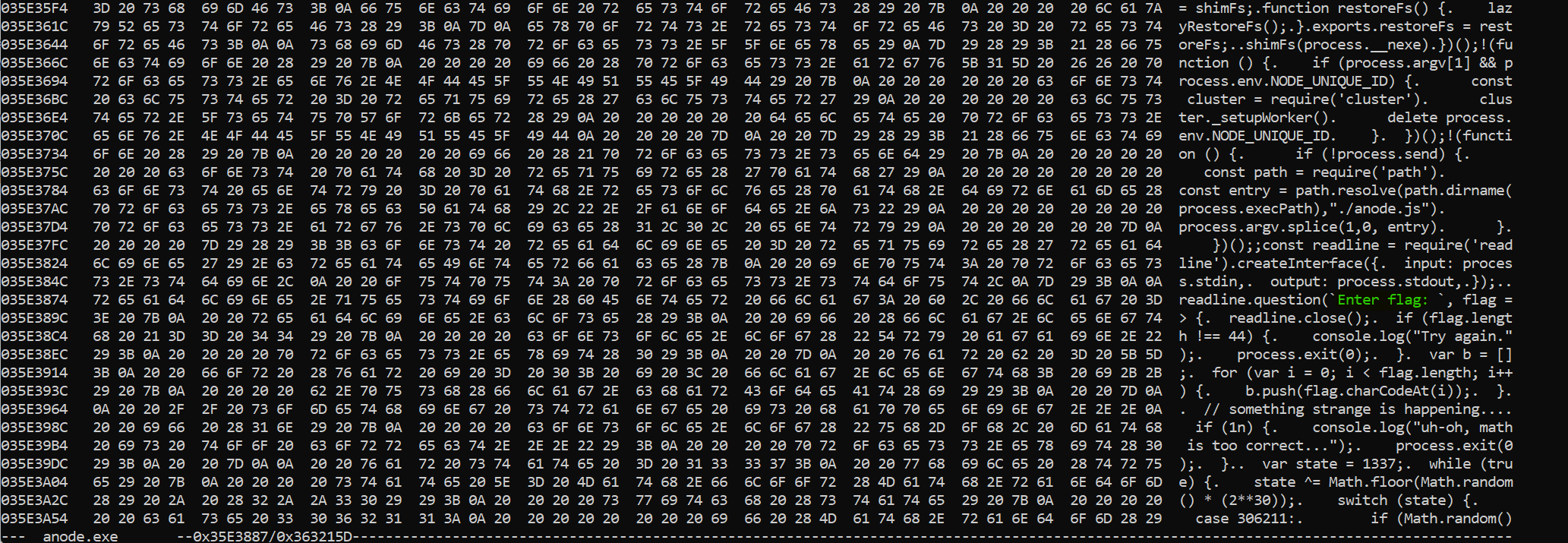

We will try to inspect strings in the file to find the Enter flag: one.

The script seems to be present in cleartext inside the binary. So we extract it easily.

const readline = require('readline').createInterface({

input: process.stdin,

output: process.stdout,

readline.question(`Enter flag: `, flag => {

readline.close();

if (flag.length !== 44) {

console.log("Try again.");

process.exit(0);

var b = [];

for (var i = 0; i < flag.length; i++) {

b.push(flag.charCodeAt(i));

}

// something strange is happening...

if (1n) {

console.log("uh-oh, math is too correct...");

process.exit(0);

}

var state = 1337;

while (true) {

state ^= Math.floor(Math.random() * (2**30));

switch (state) {

case 306211:

if (Math.random() < 0.5) {

b[30] -= b[34] + b[23] + b[5] + b[37] + b[33] + b[12] + Math.floor(Math.random() * 256);

b[30] &= 0xFF;

} else {

b[26] -= b[24] + b[41] + b[13] + b[43] + b[6] + b[30] + 225;

b[26] &= 0xFF;

}

...

default:

console.log("uh-oh, math.random() is too random...");

process.exit(0);

}

break;

var target = [106, 196, 106, 178, 174, 102, 31, 91, 66, 255, 86, 196, 74, 139, 219, 166, 106, 4, 211, 68, 227, 72, 156, 38, 239, 153, 223, 225, 73, 171, 51, 4, 234, 50, 207, 82, 18, 111, 180, 212, 81, 189, 73, 76];

if (b.every((x,i) => x === target[i])) {

console.log('Congrats!');

} else {

console.log('Try again.');

}

<nexe~~sentinel>

We observed the presence of the nexe sentinel, which is a reference to the nexe project. nexe is a packer for JavaScript scripts, that intends to transform any script in a standalone application.

So once extracted, we tested the script with a recent version of Node. The first thing we noted is the length of the input flag must be 44, so let’s try supplying a 44 characters long flag:

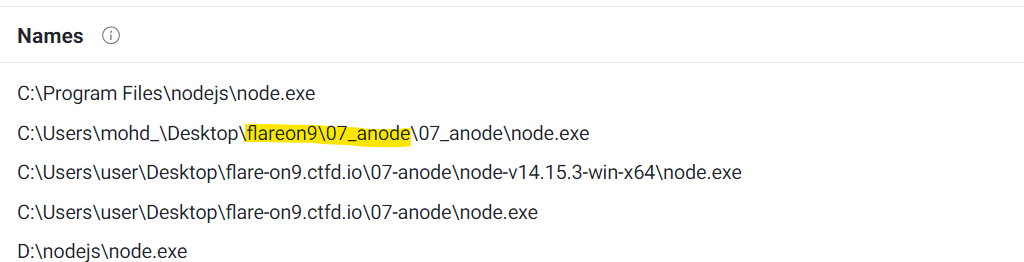

After extracting the exact version of node used by the challenges, 14.15.3, we downloaded the same hash using VirusTotal. And in the details of the hash we observed that we are not the first using this hash for the flareon :

The next is to diffing the two binaries, using bindiff, and we found a lot of diff. So we decided to compare with the one used by nexe as a template, available from Github.

And we spotted three functions, all related to math …

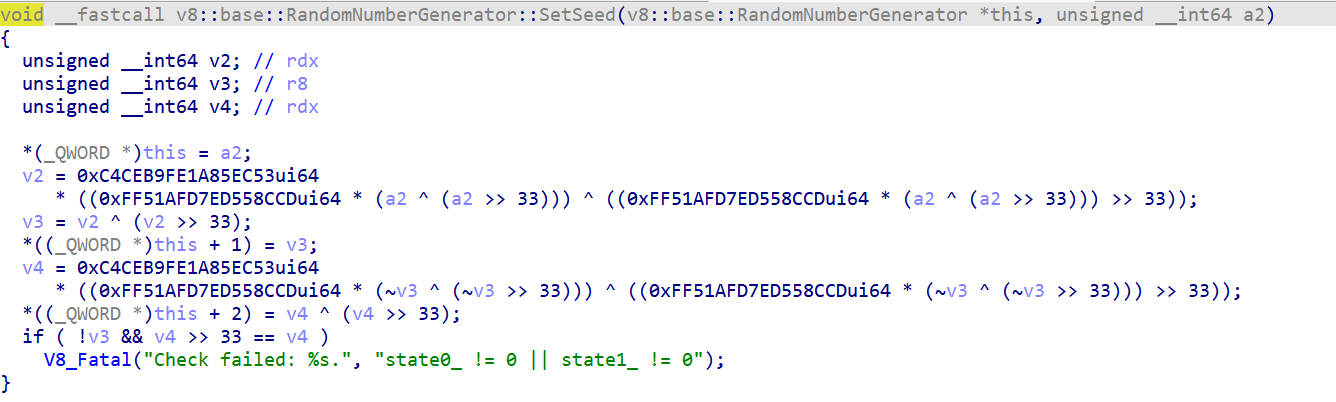

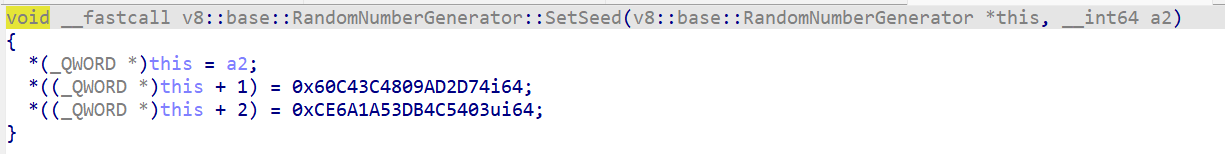

The first is v8::base::RandomNumberGenerator::SetSeed.

The original one :

The modified one :

We also observed the same modification on MathRandom::RefillCache function.

These modifications set a static feed for the Math.random function, this is why the script above becomes predictable!

The last modified function is Literal::ToBooleanIsTrue. Modifications change the way the javascript engine interprets a different kind of object in an if expression.

This is why the script made the following test at the very beginning:

if (1n) {

console.log("uh-oh, math is too correct...");

process.exit(0);

}

So we decided to clone the node.exe at the tag v14.15.3 and apply the following patch :

diff --git a/deps/v8/src/ast/ast.cc b/deps/v8/src/ast/ast.cc

index 651508b677..568732079b 100644

--- a/deps/v8/src/ast/ast.cc

+++ b/deps/v8/src/ast/ast.cc

@@ -1013,7 +1013,7 @@ template EXPORT_TEMPLATE_DEFINE(V8_EXPORT_PRIVATE)

bool Literal::ToBooleanIsTrue() const {

switch (type()) {

case kSmi:

- return smi_ != 0;

+ return smi_ == 0;

case kHeapNumber:

return DoubleToBoolean(number_);

case kString:

@@ -1031,7 +1031,7 @@ bool Literal::ToBooleanIsTrue() const {

// Skip over any radix prefix; BigInts with length > 1 only

// begin with zero if they include a radix.

for (size_t i = (bigint_str[0] == '0') ? 2 : 0; i < length; ++i) {

- if (bigint_str[i] != '0') return true;

+ if (bigint_str[i] == '0') return true;

}

return false;

}

diff --git a/deps/v8/src/base/utils/random-number-generator.cc b/deps/v8/src/base/utils/random-number-generator.cc

index 61b78f1bdf..ad6d6fe783 100644

--- a/deps/v8/src/base/utils/random-number-generator.cc

+++ b/deps/v8/src/base/utils/random-number-generator.cc

@@ -213,8 +213,8 @@ int RandomNumberGenerator::Next(int bits) {

void RandomNumberGenerator::SetSeed(int64_t seed) {

initial_seed_ = seed;

- state0_ = MurmurHash3(bit_cast<uint64_t>(seed));

- state1_ = MurmurHash3(~state0_);

+ state0_ = uint64_t{0x60C43C4809AD2D74};//MurmurHash3(bit_cast<uint64_t>(seed));

+ state1_ = uint64_t{0xCE6A1A53DB4C5403};//MurmurHash3(~state0_);

CHECK(state0_ != 0 || state1_ != 0);

}

diff --git a/deps/v8/src/numbers/math-random.cc b/deps/v8/src/numbers/math-random.cc

index d45b4d0a5f..c53bfc8708 100644

--- a/deps/v8/src/numbers/math-random.cc

+++ b/deps/v8/src/numbers/math-random.cc

@@ -49,8 +49,10 @@ Address MathRandom::RefillCache(Isolate* isolate, Address raw_native_context) {

} else {

isolate->random_number_generator()->NextBytes(&seed, sizeof(seed));

}

- state.s0 = base::RandomNumberGenerator::MurmurHash3(seed);

- state.s1 = base::RandomNumberGenerator::MurmurHash3(~seed);

+ //state.s0 = base::RandomNumberGenerator::MurmurHash3(seed);

+ //state.s1 = base::RandomNumberGenerator::MurmurHash3(~seed);

This patch matches all modifications made by the authors of the challenge.

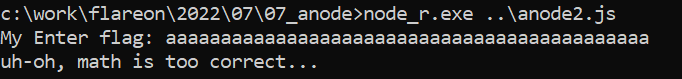

Once built we can now run the script as expected!

We now have a perfect environment to test and trace our javascript file!

We made some modifications to trace which frame is executing and the state of the random generator state :

The first thing we made, we replaced the Math.random function with a wrapper that will log the number on the console output :

function math_floor(a)

{

var tmp = Math.floor(a);

console.error("floor " + tmp);

return tmp;

}

Then we put a console.trace() instruction in each branch to trace which frames are executed :

case 22221850:

if (1052707195) { console.trace(); // <--- we are tracing !

b[13] ^= (b[30] + b[33] + b[28] + b[32] + b[12] + b[41] + math_floor(Math.random() * 256)) & 0xFF;

} else { console.trace(); // <--- we are tracing !

b[2] ^= (b[29] + b[1] + b[26] + b[42] + b[12] + b[10] + 81) & 0xFF;

}

state = 554472923;

continue;

In the end, we produced output like :

...

Trace

at c:\work\flareon\2022\07\aanode.js:4098:26

at Interface._onLine (readline.js:335:5)

at Interface._line (readline.js:666:8)

at Interface._ttyWrite (readline.js:1010:14)

at ReadStream.onkeypress (readline.js:213:10)

at ReadStream.emit (events.js:315:20)

at emitKeys (internal/readline/utils.js:345:14)

at emitKeys.next (<anonymous>)

at ReadStream.onData (readline.js:1144:36)

at ReadStream.emit (events.js:315:20)

floor 241

floor 679960405

...

We made a script able to parse this trace file to produce a version without any branch obfuscation and call of Math.random :

b[29] -= b[37] + b[23] + b[22] + b[24] + b[26] + b[10] + 7;

b[29] &= 0xFF;

b[39] += b[34] + b[2] + b[1] + b[43] + b[20] + b[9] + 79;

b[39] &= 0xFF;

b[28] ^= (b[1] + b[23] + b[37] + b[31] + b[43] + b[42] + 245) & 0xFF;

b[19] ^= (b[26] + b[0] + b[40] + b[37] + b[23] + b[32] + 255) & 0xFF;

...

This algorithm is a composition of bijection, which accepts an inverse $(f \cdot g)^{-1} = f^{-1} \cdot g^{-1}$.

The inverse of += is -=, the inverse -= is += and the inverse of ^= is itself. At the end of the original script, we have the final state of the input vector, which will become our initial vector!

We have to apply it in reverse order, so we made the following python script :

b = [106, 196, 106, 178, 174, 102, 31, 91, 66, 255, 86, 196, 74, 139, 219, 166, 106, 4, 211, 68, 227, 72, 156, 38, 239, 153, 223, 225, 73, 171, 51, 4, 234, 50, 207, 82, 18, 111, 180, 212, 81, 189, 73, 76]

b[39] -= b[18] + b[16] + b[8] + b[19] + b[5] + b[23] + 36

b[39] &= 0xFF

b[22] -= b[16] + b[18] + b[7] + b[23] + b[1] + b[27] + 50

b[22] &= 0xFF

b[34] -= b[35] + b[40] + b[13] + b[41] + b[23] + b[25] + 14

b[34] &= 0xFF

b[21] -= b[39] + b[6] + b[0] + b[33] + b[8] + b[40] + 179

b[21] &= 0xFF

...

b[29] += b[37] + b[23] + b[22] + b[24] + b[26] + b[10] + 7

b[29] &= 0xFF

print("".join([chr(x) for x in b]))

And Mathematic magic happened :

n0t_ju5t_A_j4vaSCriP7_ch4l1eng3@flare-on.com

08 - backdoor 🔗

I’m such a backdoor, decompile me why don’t you…

Files :

FlareOn.Backdoor.exe

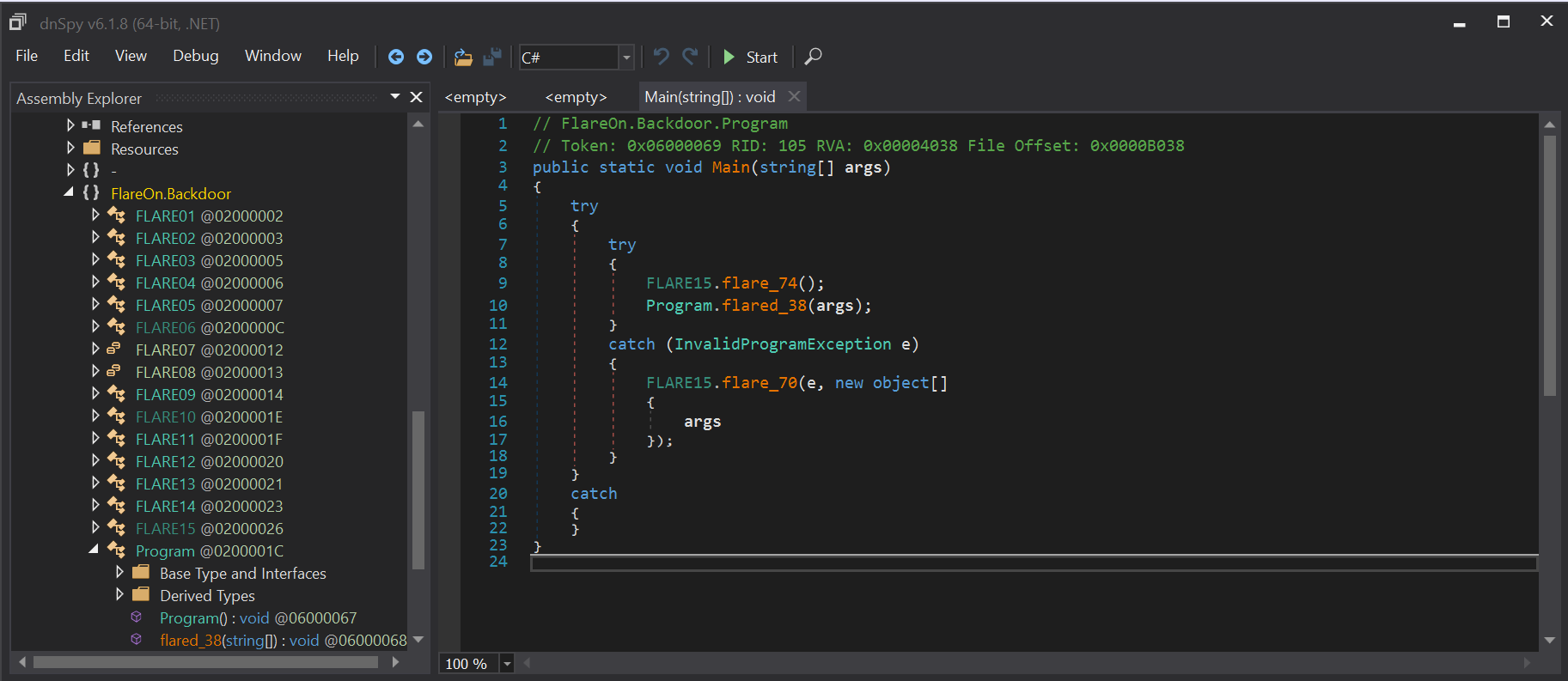

The payload is a .NET payload, so let’s start with the best .NET disassembler, aka dnSpy.

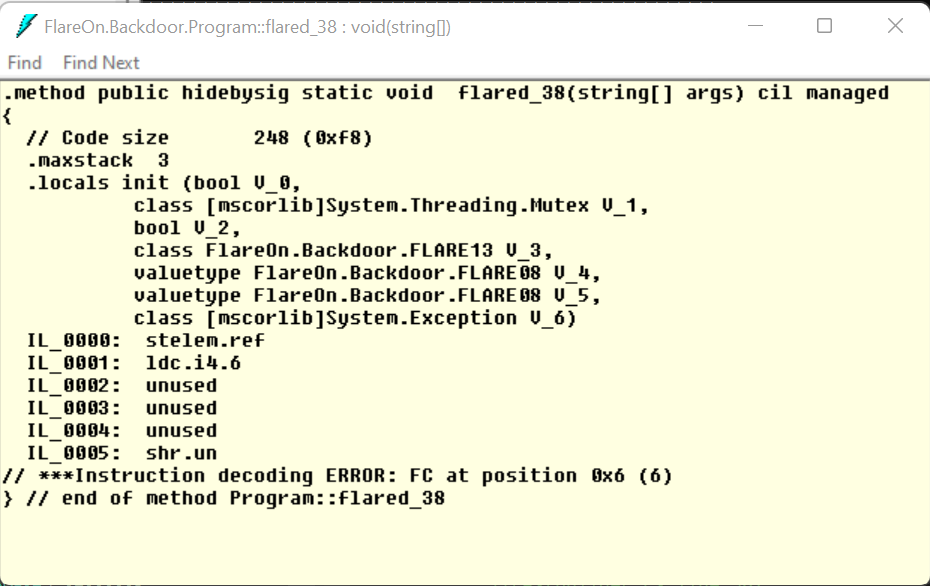

The FLARE15.Flare74() is a function that will load some useful resources for the rest of the execution. Then take a look at the Program.flared_38 and …

Ok…

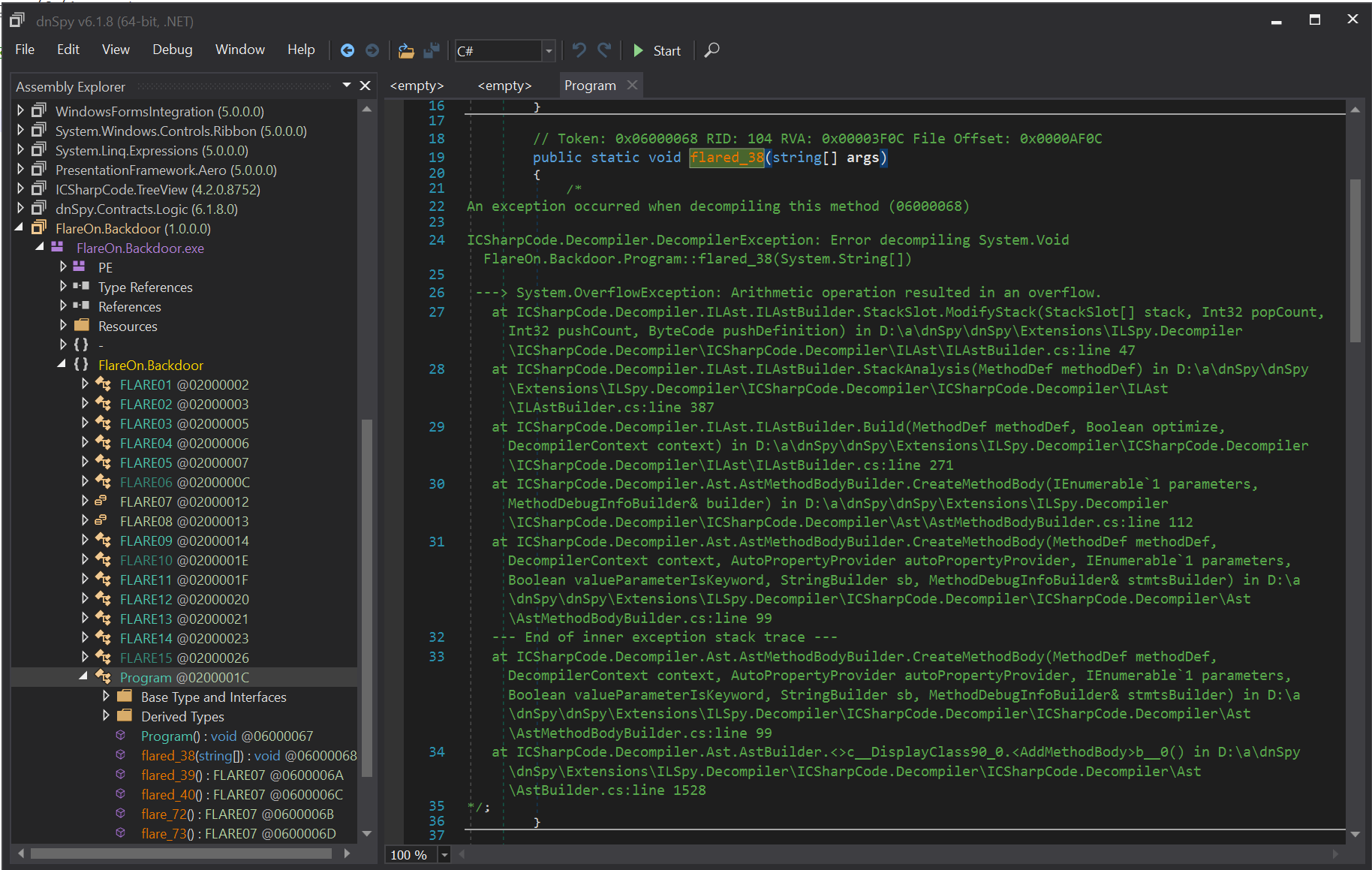

Ok, let’s take a look into a raw disassembler ILDasm, which is part of the visual studio toolset.

Ok…

So let’s try to run it !!!

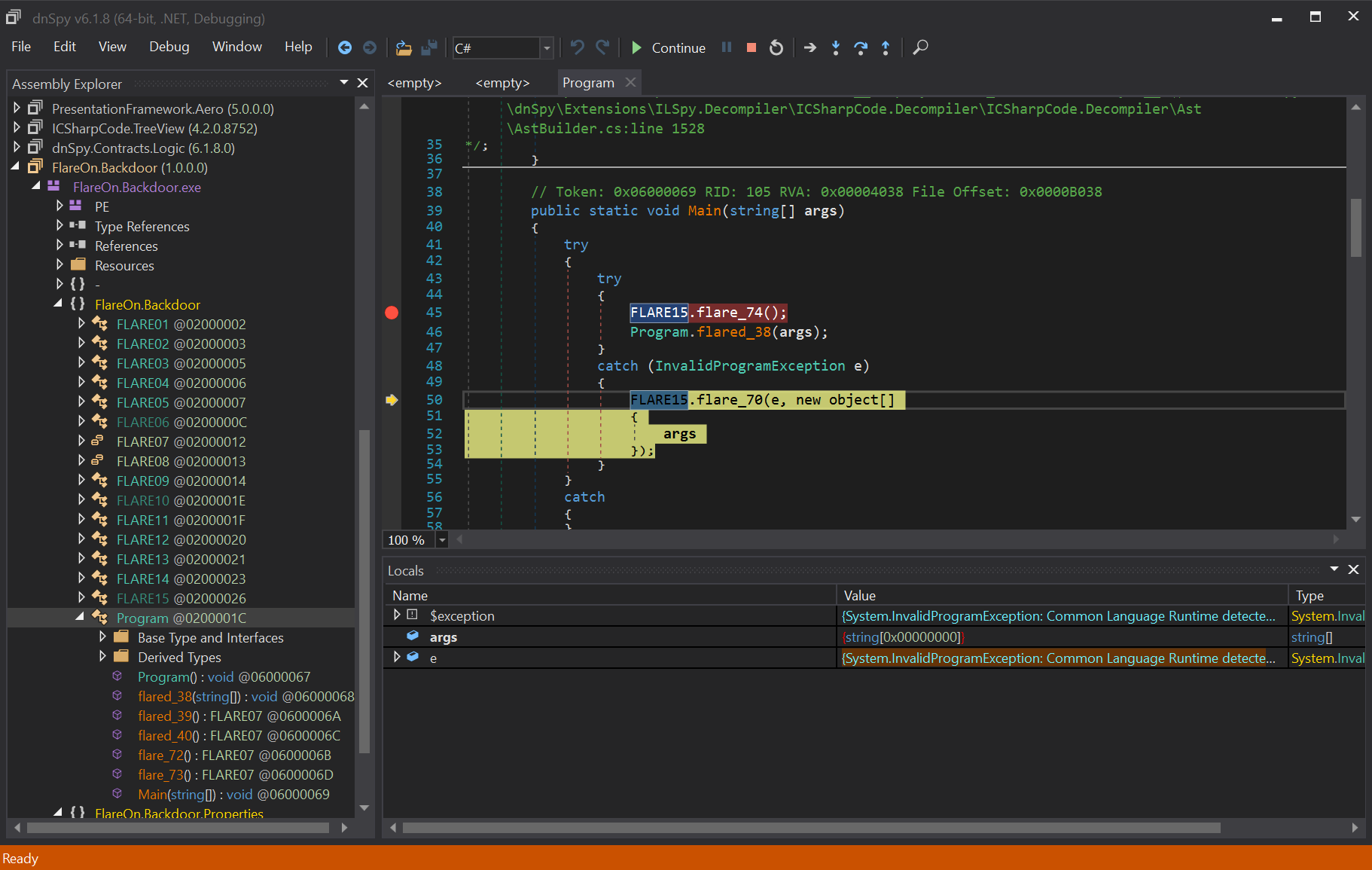

When invoking Program.flared_38, an InvalidProgramException exception is launched. This exception is part of the CLR, when trying to run an invalid program. This is what we saw in the disassembler.

It’s not a disassembler obfuscation, it’s also a bad program. Now take a look at the exception handler, which seems to track the calling context.

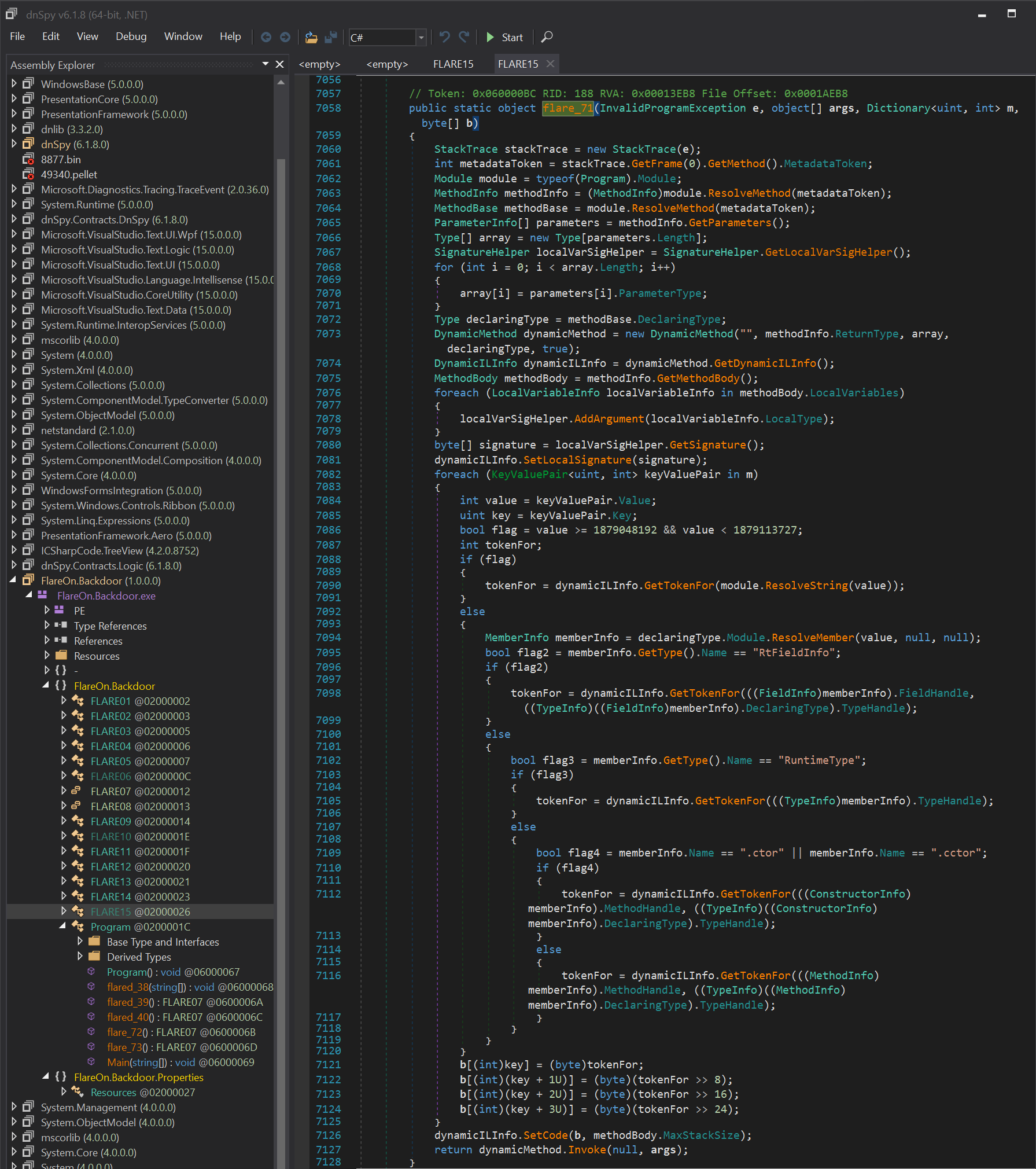

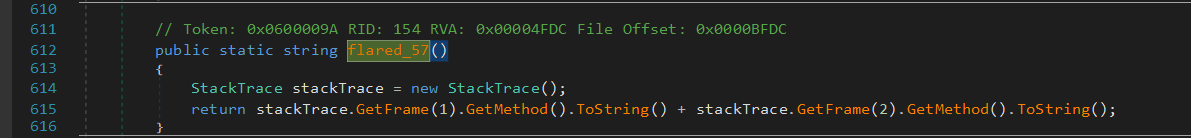

There is a naming convention, the XXX.flared_XX functions seem to be obfuscated, and XXX.flare_XX are normal functions. We went directly to the FLARE15.flare_71(e, m, b) which is called from the exception handler in a few function :

This function will retrieve the calling context, which function generates an exception, by inspecting the stack trace of the exception e.

Then it will dynamically create a new function from the parameters m and b, and call it with the original parameter.

// Retrieve calling context of the obfuscated function

StackTrace stackTrace = new StackTrace(e);

int metadataToken = stackTrace.GetFrame(0).GetMethod().MetadataToken;

Module module = typeof(Program).Module;

MethodInfo methodInfo = (MethodInfo)module.ResolveMethod(metadataToken);

MethodBase methodBase = module.ResolveMethod(metadataToken);

// Create new methad with its own token namespace

DynamicMethod dynamicMethod = new DynamicMethod("", methodInfo.ReturnType, array, declaringType, true);

DynamicILInfo dynamicILInfo = dynamicMethod.GetDynamicILInfo();

// patching tokens following the m parameters

...

dynamicILInfo.SetCode(b, methodBody.MaxStackSize);

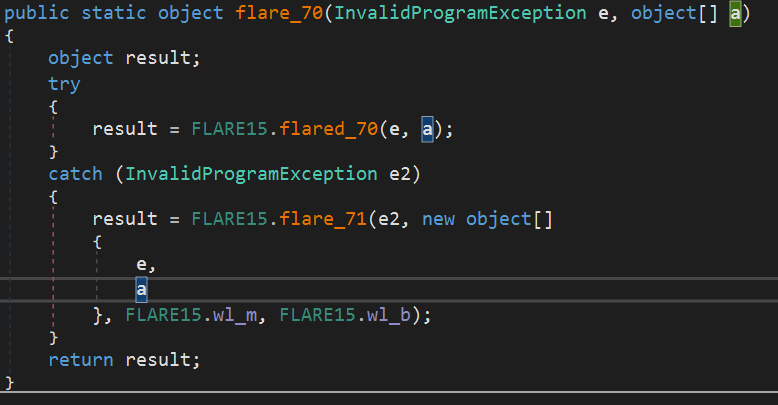

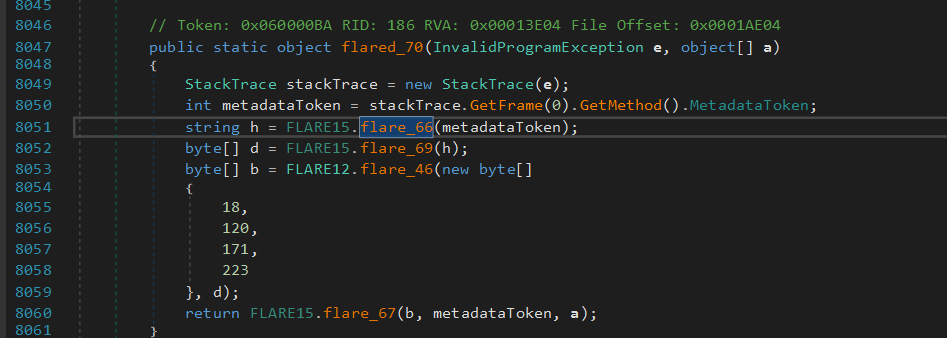

For example, the function FLARE15.flared_70 is desobfuscated using FLARE15.wl_m, FLARE15.wl_b global variables.

The code will patch the different token id used by the function, and try to do a mapping between the local token id and global token id of the assembly.

To better understand what is done by the loader, we have to understand what are tokens in .NET Tokens are used to uniquely identify any kind of .NET object (Methods, Assembly, …) inside an Assembly.

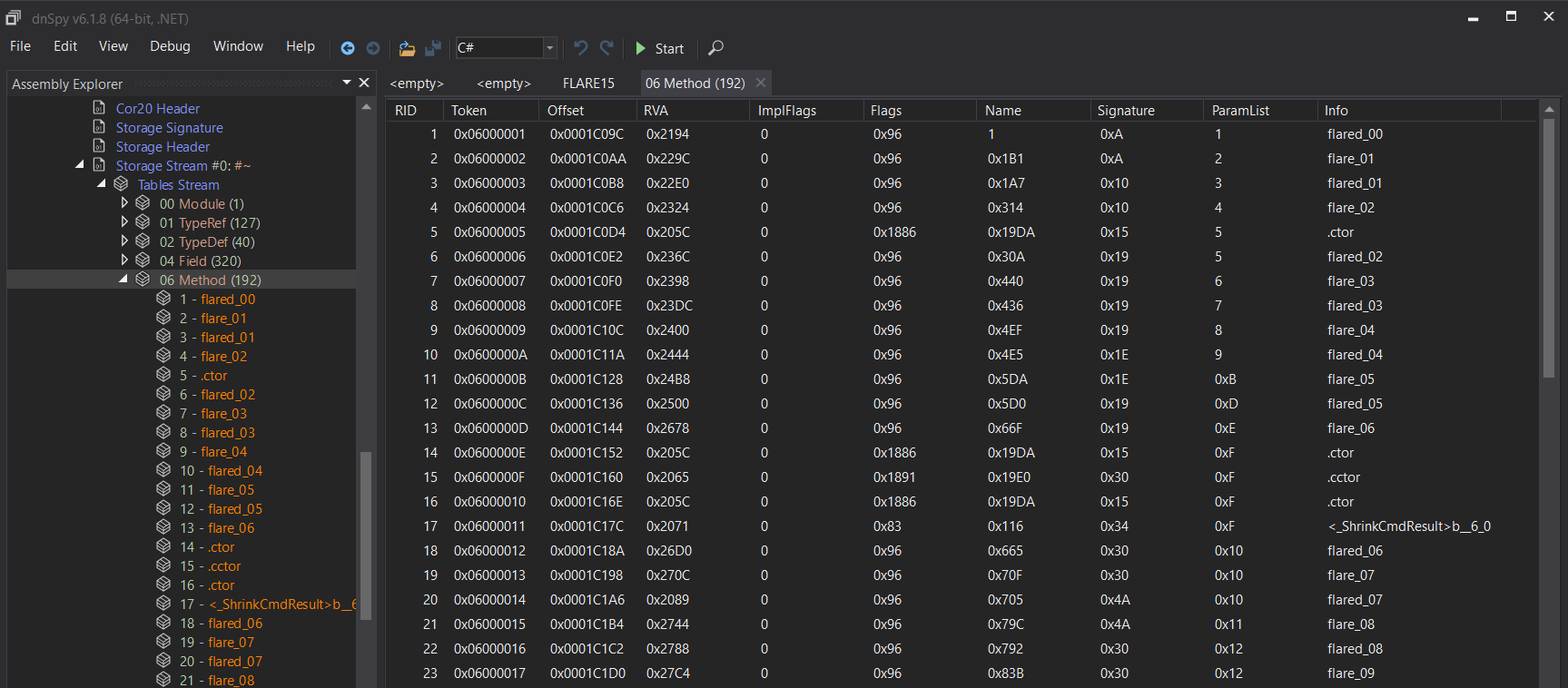

We can see all tokens for one assembly by inspecting the Storage stream #0 in PE header :

DynamicILInfo allows you to create a private token namespace local to a function.

We can make a parallel with a classic payload loader, where the m parameter is the relocation table, and b parameter is the bytecode.

We also observed that the space available inside the PE for each obfuscated function is the same sized as the deobfuscated bytecode.

For example, the FLARE15.flared_70, the length of FLARE15.wl_b is 85 bytes, and the space in the file is also equal to 85 !!!

So if we patch the PE file we can create a deobfuscated one!

We created a Patcher assembly that will use the FlareOn.Backdoor.exe. From our main, we will invoke the function FLARE15.flare_74() to load resources, then we create a function Compile that is equivalent to FLARE15.flare_71(e, m, b), but patching the token id using the global one!

static Byte[] Compile(MethodBase baseMethod, Dictionary<uint, int> m, byte[] b)

{

int metadataToken = baseMethod.MetadataToken;

Module module = typeof(FlareOn.Backdoor.Program).Module;

MethodInfo methodInfo = (MethodInfo)module.ResolveMethod(metadataToken);

MethodBase methodBase = module.ResolveMethod(metadataToken);

ParameterInfo[] parameters = methodInfo.GetParameters();

Type[] array = new Type[parameters.Length];

SignatureHelper localVarSigHelper = SignatureHelper.GetLocalVarSigHelper();

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

array[i] = parameters[i].ParameterType;

}

Type declaringType = methodBase.DeclaringType;

DynamicMethod dynamicMethod = new DynamicMethod("", methodInfo.ReturnType, array, declaringType, true);

DynamicILInfo dynamicILInfo = dynamicMethod.GetDynamicILInfo();

MethodBody methodBody = methodInfo.GetMethodBody();

foreach (LocalVariableInfo localVariableInfo in methodBody.LocalVariables)

{

localVarSigHelper.AddArgument(localVariableInfo.LocalType);

}

byte[] signature = localVarSigHelper.GetSignature();

dynamicILInfo.SetLocalSignature(signature);

foreach (KeyValuePair<uint, int> keyValuePair in m)

{

int value = keyValuePair.Value;

uint key = keyValuePair.Key;

bool flag = value >= 1879048192 && value < 1879113727;

int tokenFor = value;

b[(int)key] = (byte)tokenFor;

b[(int)(key + 1U)] = (byte)(tokenFor >> 8);

b[(int)(key + 2U)] = (byte)(tokenFor >> 16);

b[(int)(key + 3U)] = (byte)(tokenFor >> 24);

}

return b;

}

Then we invoked the function and write the generated bytecode at the correct offset for each function. For example, the function FLARE15.flared_70 :

b = Compile(typeof(FLARE15).GetMethod("flared_70"), FLARE15.wl_m, FLARE15.wl_b);

using (var source = File.OpenWrite("C:\\work\\flareon\\2022\\08\\08_backdoor\\FlareOn.Backdoor_patched_1.exe"))

{

source.Seek(0x1ae10, SeekOrigin.Begin);

source.Write(b, 0, b.Length);

}

This function is invoked to patch :

- FLARE15.flared_66

- FLARE15.flared_67

- FLARE15.flared_68

- FLARE15.flared_69

- FLARE15.flared_70

- FLARE09.flared_35

- FLARE12.flared_47

Tada!

At this point we have a few functions (7) deobfuscated, but we still have a lot of them unavailable inside dnSpy.

Let’s take look inside the new one!

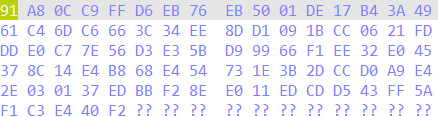

These functions are used to make the second level of obfuscation. The goal is not so far from the previous one. The difference is the location of the deobfuscated bytecode. To load bytecode, the algorithm will compute the hash of the signature of the target function, find a section in the PE named with the beginning of hash, and decrypt it using RC4 algorithm and a static key:

FLARE15.flared_66is in charge to compute a hash from the metadata of .NET function.FLARE15.flared_69is in charge to find the right section in the PEFLARE12.flared_47is a RC4 encryption methodFLARE15.flared_67is equivalent toFLARE15.flare_71function, but with bytecode, parser to patch without the need for a “relocation table”.

So once again, the available size in the PE for each function is enough to include deobfuscated bytecode.

Back to our Patcher assembly, we created a function that does exactly the same job, except for the resolution of the token and reusing the global token table of the assembly.

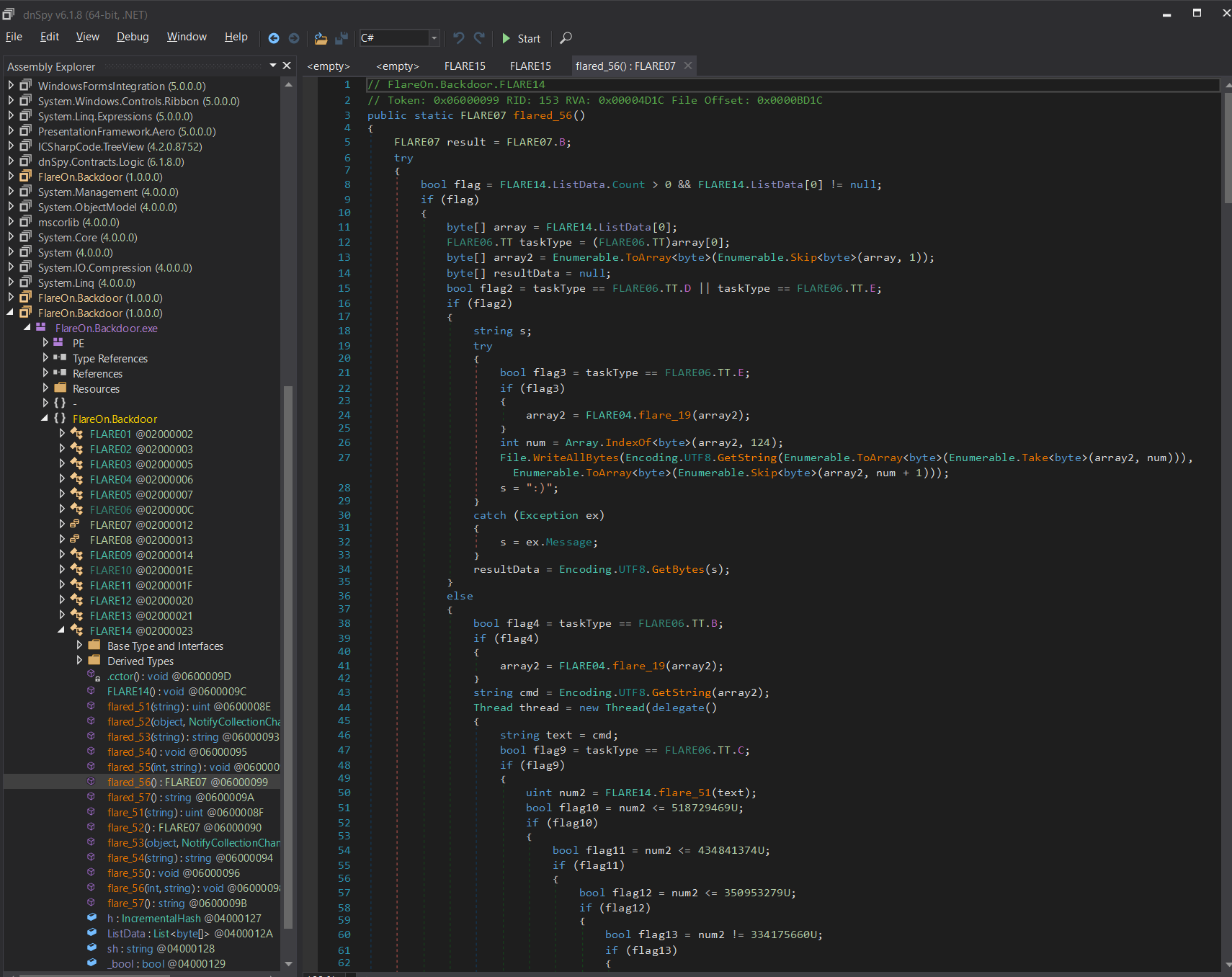

For example, the function FLARE14.flared_56 :

public static byte[] patch_function(MethodBase baseMethod)

{

var h = hash(baseMethod.MetadataToken);

var b = find_section(h);

return patch_meta(decode(new byte[4] { 18, 120, 171, 223 }, b));

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

...

b = patch_function(typeof(FLARE14).GetMethod("flared_56"));

using (var source = File.OpenWrite("C:\\work\\flareon\\2022\\08\\08_backdoor\\FlareOn.Backdoor_patched_1.exe"))

{

source.Seek(0xbd28, SeekOrigin.Begin);

source.Write(b, 0, b.Length);

}

...

}

And Tada Tada!

And start the understanding of the backdoor…

So the backdoor seems to be trying to reach a random DNS name and check some conditions, like the last digit of the IP address has to be greater than 128… It keeps track of the number of tries by writing its state in a local file. By setting the correct number you can predict the next DNS name…

But all this stuff is not needed to understand the challenge. The backdoor is based on a state machine implemented inside the FLARE13 object.

By understanding the automata, you reach the interesting function FLARE14.flared_56. This function handles commands from the C&C, but with something more.

Each time the C&C sends a command, the function also checks a particular collection ObservableCollection named FLARE15.c:

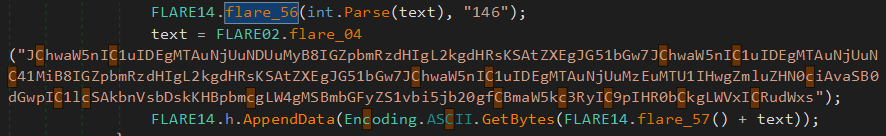

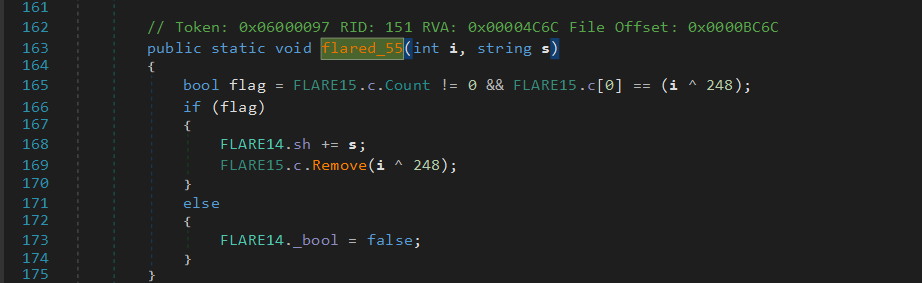

The FLARE14.flare_56 function will check if the byte passed as a parameter, XORed with 248, match the next byte inside the ObservableCollection. If it’s the right one the element is removed from the list.

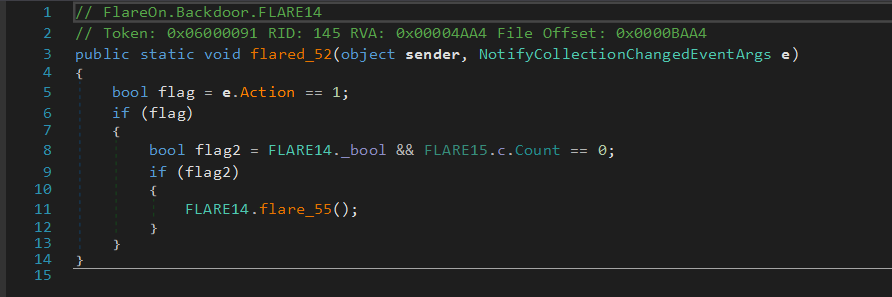

Each time an element is added or removed from the list, a callback is invoked. This function will check if the collection is empty, and if it’s true, a file is written on the disk.

And we guessed the file is our goal. The ObservableCollection is used as a State Machine too. To decrypt the file we have to have the FLARE14.h hash which is computed from an action performed by the backdoor plus a salt:

FLARE14.h.AppendData(Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(FLARE14.flare_57() + text))

The salt is computed by FLARE14.flare_57() by checking the calling context :

So we emulated all the automata inside my Packer assembly :

public static void soluce()

{

FLARE14.h = IncrementalHash.CreateHash(HashAlgorithmName.SHA256);

var foo = FLARE14.flare_57();

var text = "2";

FLARE14.flare_56(int.Parse(text), "d7d");

text = FLARE02.flare_04("RwBlAHQALQBOAGUAdABOAGUAaQBnAGgAYgBvAHIAIAAtAEEAZABkAHIAZQBzAHMARgBhAG0AaQBsAHkAIABJAFAAdgA0ACAAfAAgAFMAZQBsAGUAYwB0AC0ATwBiAGoAZQBjAHQAIAAiAEkAUABBAEQARAByAGUAcwBzACIA");

FLARE14.h.AppendData(Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(foo + text));

text = "10";

FLARE14.flare_56(int.Parse(text), "f38");

text = "hostname";

FLARE14.h.AppendData(Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(foo + text));

...

byte[] d = find_section(FLARE14.flare_54(FLARE14.sh));

byte[] hashAndReset = FLARE14.h.GetHashAndReset();

byte[] array = FLARE12.flare_46(hashAndReset, d);

using (FileStream fileStream = new FileStream("c:\\work\\flareon\\2022\\08\\res.gif", FileMode.Create, FileAccess.Write, FileShare.Read))

{

fileStream.Write(array, 0, array.Length);

}

}

And it’s NOT working…

Wait wait wait, in our Packer assembly we referenced the deobfuscated backdoor, so we totally changed the calling context of the function, and the salt is not the same.

So by referencing the original assembly :

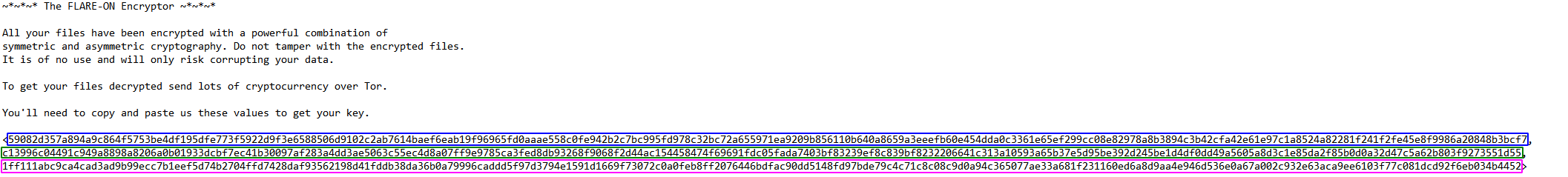

09 - encryptor 🔗

You’re really crushing it to get this far. This is probably the end for you. Better luck next year!

Files:

flareon.exeSuspiciousFile.txt.Encrypted

Smells like ransomware and crypto!

Let’s run it through Detect-It-Easy:

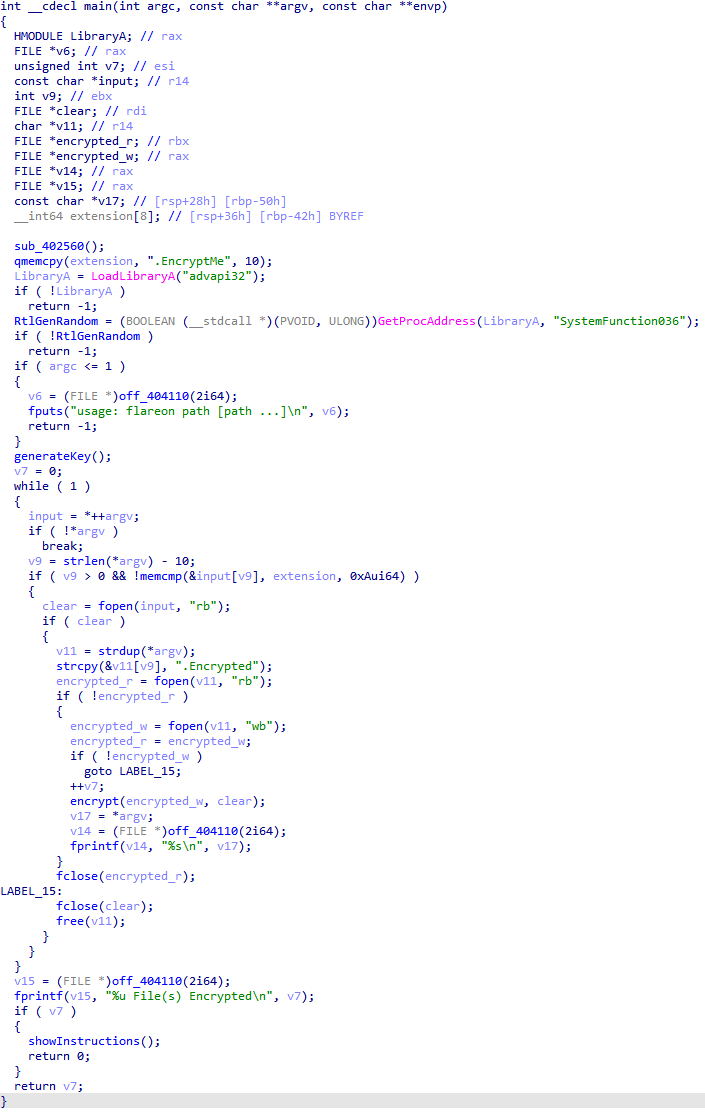

Of course, running it directly from a console didn’t do anything.

First we had to create our own encrypted file with a known clear text so we could try to decrypt it, and flareon.exe only encrypted files ending by .EncryptMe:

-

./test/TryMe.txt.EncryptMe:

ABC -

> flareon.exe ./test/ -

./test/TryMe.txt.Encrypted

The encrypted file was clearly separated in 5 different parts. The first one was obviously our encrypted text, and the 4 others had to help the gang to decrypt files.

A HOW_TO_DECRYPT.txt file was also created on the user’s desktop:

For some reason, the last part of the .Encrypted file wasn’t here…

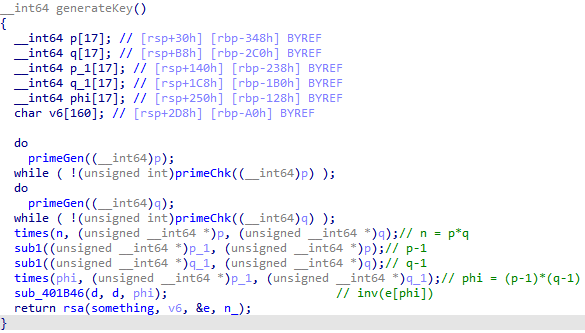

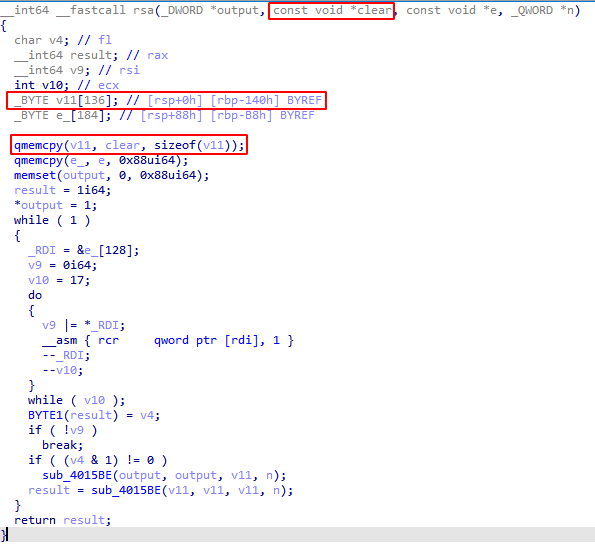

Let’s look at the generateKey() function:

It encrypts something (truly not important) with e = 5 as a static exponent and n_ as a static modulus (yes, they didn’t use the n they just computed…).

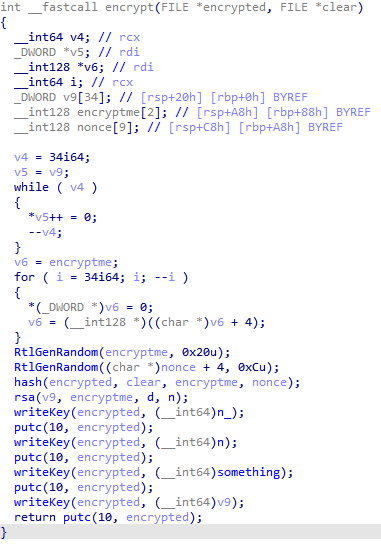

Then, back to the main, the program created the .Encrypted file, and executed the encrypt() function, passing the .Encrypted file descriptor and the clear text in argument.

Here comes the fun part:

- It generated a random number

encryptmeon 32 bytes and stored it in a 2 * 16 bytes array - Then, it generated a random number

nonceon 12 bytes and stored 4 * 0 bytes + the random 12 bytes in a 9 * 16 bytes array - After that, it encrypted

cleartoencryptedin Salsa20 and wrote it in the file - To finish, it encrypted the first 32 random bytes in RSA with the previously generated private key

das exponent, and the previously generatednas modulus

wait…

They encrypted their clear text with their private key!

After that, they wrote n_, n, something, and the RSA encrypted message in the file.

We had the modulus n, we also had the static exponent e, so we just had to do C^e[n] to decrypt the 32 random bytes!

SuspiciousFile.txt.Encrypted

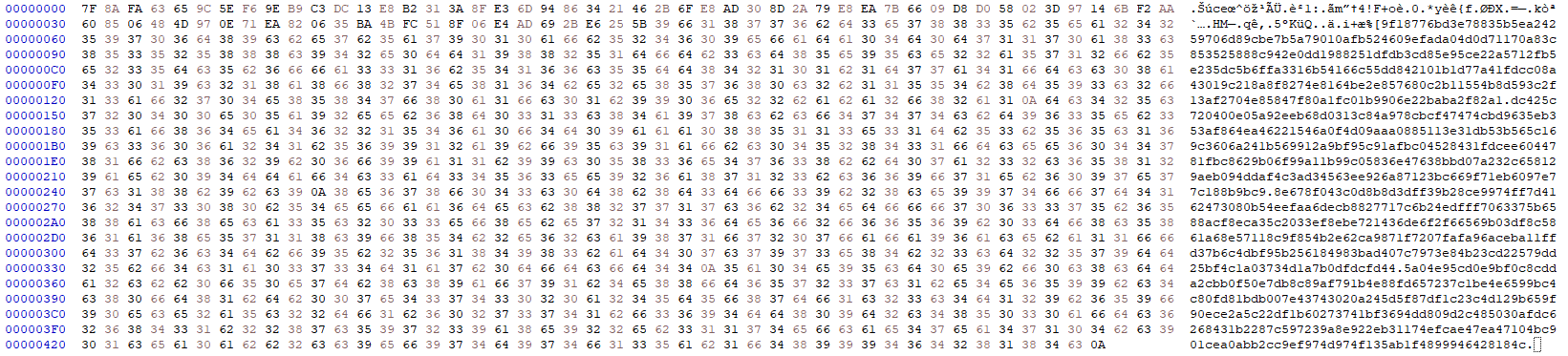

m = 0x5a04e95cd0e9bf0c8cdda2cbb0f50e7db8c89af791b4e88fd657237c1be4e6599bc4c80fd81bdb007e43743020a245d5f87df1c23c4d129b659f90ece2a5c22df1b60273741bf3694dd809d2c485030afdc6268431b2287c597239a8e922eb31174efcae47ea47104bc901cea0abb2cc9ef974d974f135ab1f4899946428184c

n = 0xdc425c720400e05a92eeb68d0313c84a978cbcf47474cbd9635eb353af864ea46221546a0f4d09aaa0885113e31db53b565c169c3606a241b569912a9bf95c91afbc04528431fdcee6044781fbc8629b06f99a11b99c05836e47638bbd07a232c658129aeb094ddaf4c3ad34563ee926a87123bc669f71eb6097e77c188b9bc9

e = 0x10001

print(hex(pow(m,e,n)))

0x958f924dfe4033c80ffc490200000000989b32381e5715b4a89a87b150a5d528c943a775e7a2240542fc392aa197b001

But… How long is that? Well, it’s 48 bytes long… But how come?

The RSA function encrypted 136 bytes of the clear text, but it passed a 32 bytes random number, so it overflowed to the 4 * 0 bytes + 12 Bytes nonce! We recovered the secret, the nonce, and we had the encrypted text!

from Crypto.Cipher import ChaCha20

m = 0x5a04e95cd0e9bf0c8cdda2cbb0f50e7db8c89af791b4e88fd657237c1be4e6599bc4c80fd81bdb007e43743020a245d5f87df1c23c4d129b659f90ece2a5c22df1b60273741bf3694dd809d2c485030afdc6268431b2287c597239a8e922eb31174efcae47ea47104bc901cea0abb2cc9ef974d974f135ab1f4899946428184c

n = 0xdc425c720400e05a92eeb68d0313c84a978cbcf47474cbd9635eb353af864ea46221546a0f4d09aaa0885113e31db53b565c169c3606a241b569912a9bf95c91afbc04528431fdcee6044781fbc8629b06f99a11b99c05836e47638bbd07a232c658129aeb094ddaf4c3ad34563ee926a87123bc669f71eb6097e77c188b9bc9

e = 0x10001

salsa = pow(m,e,n)

print(f'N = {hex(n)}')

print(f'E = {hex(e)}')

print(f'M = {hex(m)}')

print(f'SALSA20 = {hex(salsa)}')

secret = 0x989b32381e5715b4a89a87b150a5d528c943a775e7a2240542fc392aa197b001.to_bytes(32, 'little')

nonce = 0x958f924dfe4033c80ffc4902.to_bytes(12, 'little')

cipher = ChaCha20.new(key=secret, nonce=nonce)

plaintext = 0x7F8AFA63659C5EF69EB9C3DC13E8B2313A8FE36D94863421462B6FE8AD308D2A79E8EA7B6609D8D058023D97146BF2AA608506484D970E71EA820635BA4BFC518F06E4AD692BE6255B.to_bytes(73, 'big')

print(cipher.decrypt(plaintext).decode())

N = 0xdc425c720400e05a92eeb68d0313c84a978cbcf47474cbd9635eb353af864ea462 <snip>

E = 0x10001

M = 0x5a04e95cd0e9bf0c8cdda2cbb0f50e7db8c89af791b4e88fd657237c1be4e6599b <snip>

SALSA20 = 0x958f924dfe4033c80ffc490200000000989b32381e5715b4a89a87b150a5 <snip>

Hello!

The flag is:

R$A_$16n1n6_15_0pp0$17e_0f_3ncryp710n@flare-on.com

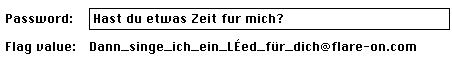

10 - Nur geträumt 🔗

This challenge is a Macintosh disk image (Disk Copy 4.2 format, for those who need to know) containing a 68K Macintosh program. You must determine the passphrase used to decode the flag contained within the application. Super ResEdit, an augmented version of Apple’s ResEdit resource editor which adds a disassembler, is also included on the disk image to help you complete the challenge, though you will likely also need to do some outside research to guess the passphrase. This application can be run on any Macintosh emulator (or any real Macintosh from as far back as a Mac Plus running System 6.0.x up to a G5 running Classic). The setup of the emulation environment is part of the challenge, so few spoilers live here, but if you want to save yourself some headaches, Mini vMac is a pretty good choice that doesn’t take much effort to get up and running compared to some other options. This application was written on a Power Macintosh 7300 using CodeWarrior Pro 5, ResEdit, and Resourcerer (my old setup from roughly 1997, still alive!). It was tested on a great many machines and emulators, and validated to run well on Mac OS from 6.0.8 through 10.4. Happy solving! Be curious!

Files:

Nur geträumt.imgREADME.txt

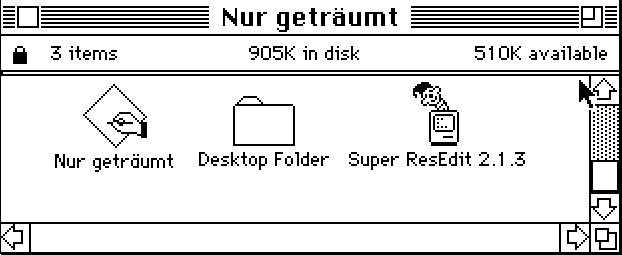

First we had to install Mini vMac, so we downloaded the version 36.04-wx64.

After finding a ROM, we followed the “Getting started with Mini vMac” article and downloaded ua608d in order to unarchive the Macintosh System Software disk images.

ua608d.exe SSW_6.0.8-1.4MB_Disk1of2.sea.bin "System Startup"

ua608d.exe SSW_6.0.8-1.4MB_Disk2of2.sea.bin "System Additions"

At that point, opening Nur geträumt.img wouldn’t work, we actually had to rename it to take off the unicode characters.

Nur geträumt:

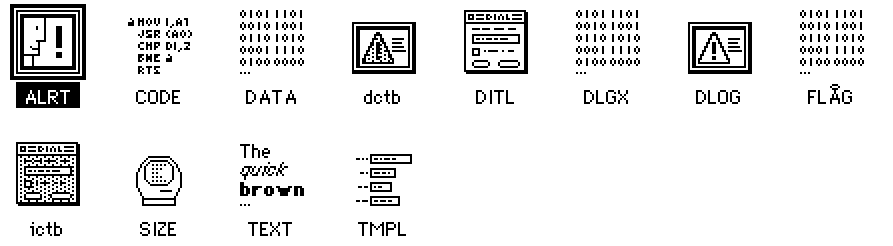

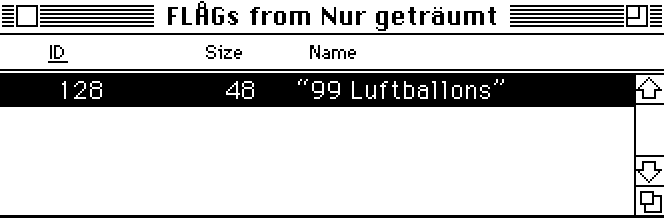

We could analyze the software with Super ResEdit 2.1.3:

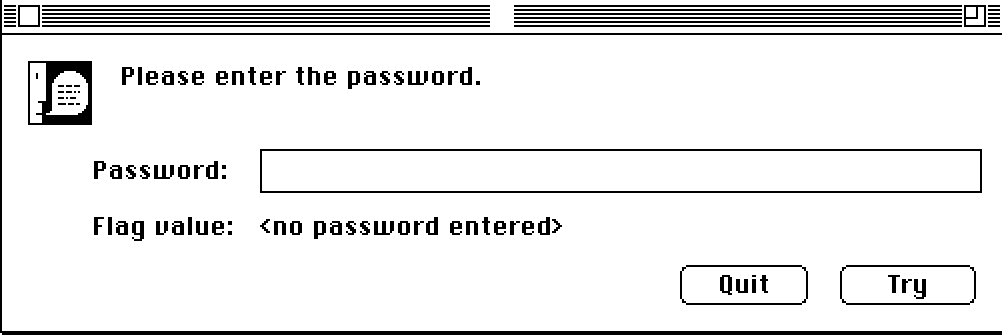

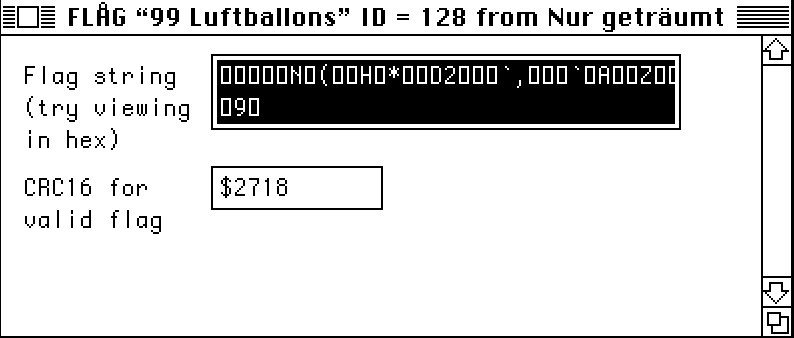

The Flag section contained the following:

We could have analyzed the assembly to reverse the whole application, but we decided to do otherwise.

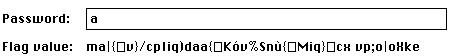

And if we entered more “a”, the output would remain the same. But we added another character:

1 byte every 2 changed… It kinda looked like a rolling XOR cipher to us.

We knew the end of the flag would be @flare-on.com, so we tried to recover the key:

“1” gave us “5”, so:

chr(ord('1') ^ ord('5') ^ ord('m')) # = 'i'

It gave us an “m”! So we tried for the “o”:

chr(ord('1') ^ ord(';') ^ ord('o')) # = 'e'

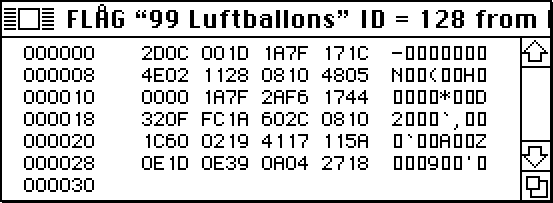

In fact, the input XORed with the output gives us the key, and the key XORed with what we guess is the output gives us the input. Here, ord('1') ^ ord('5') = 0x04 and ord('1') ^ ord(';') = 0X0A, which is exactly the same as the two last bytes of Flag before 0x2718, so…

flag = [12, 0, 29, 26, 127, 23, 28, 78, 2, 17, 40, 8, 16, 72, 5, 0, 0, 26, 127, 42, 246, 23, 68, 50, 15, 252, 26, 96, 44, 8, 16, 28, 96, 2, 25, 65, 23, 17, 90, 14, 29, 14, 57, 10, 4, 39, 24]

flare = "@flare-on.com"

output = ""

for i in range(1, len(flare)):

output = chr(ord(flare[-i]) ^ flag[-i-2]) + output

du etwas Zei

If you look online, it’s the lyrics of 99 Luftballons!

So we typed the first line of the lyrics:

The flag was the second line!

Dann_singe_ich_ein_Lied_fur_dich@flare-on.com

11 - The challenge that shall not be named 🔗

Protection, Obfuscation, Restrictions… Oh my!!

The good part about this one is that if you fail to solve it I don’t need to ship you a prize.

Files :

11.exe

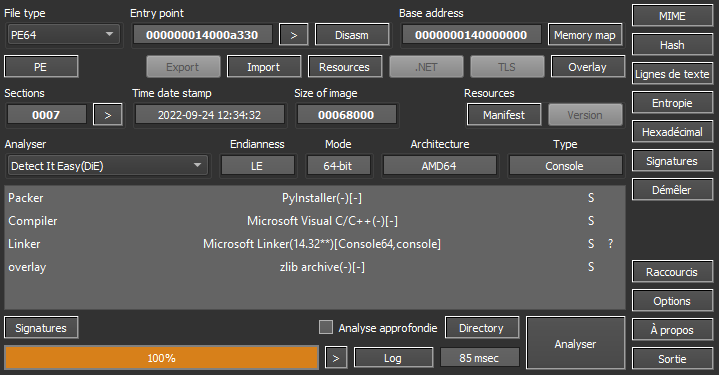

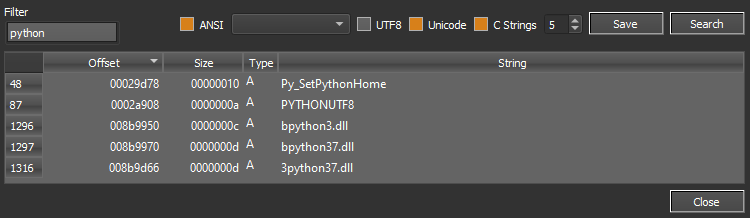

We first analyzed the PE with DIE (Detect It Easy) and noticed it was a Python script packed with PyInstaller, which packs a python application with all its dependencies.

In order to get the executed script, we used PyInstaller Extractor, but to do so, we had to find the right Python version.

Searching “python” in the strings quickly showed us a python37.dll, and ProcMon also pointed out python37.dll was loaded.

Once extracted: python3.7 pyinstxtractor.py 11.exe, the python bytecode could be found in 11.pyc. A simple way to recover the original source code was to run uncompyle6.

And then…

from pytransform import pyarmor

pyarmor(__name__, __file__, b'PYARMOR\x00\x00\x03\x07\x00B\r\r\n\t0\xe0\x02\x01\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00@\x00\x00\x00a\x02\x00\x00\x0b\x00\x00x\xa7\xf5\x80\x15\x8c\x1f\x90\xbb\x16Xu\x86\x9d\xbb\xbd\x8d\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0054$\xf1\xeb,\nY\xa9\x9b\xa5\xb3\xba\xdc\xd97\xba\x13\x0b\x89 \xd2\x14\xa7\xccH0\x9b)\xd4\x0f\xfb\xe4`\xbd\xcf\xa28\xfc\xf1\x08\x87w\x1a\xfb%+\xc1\xbe\x8b\xc0]8h\x1f\x88\xa6CB>*\xdd\xf6\xec\xf5\xe30\xf9\x856\xfa\xd9P\xc8C\xc1\xbdm\xca&\x81\xa9\xfb\x07HE\x1b\x00\x9e\x00a\x0c\xf2\xd0\x87\x0c<\xf8\xddZf\xf1,\x84\xce\r\x14*s\x11\x82\x88\x8d\xa7\x00k\xd9s\xae\xd3\xfc\x16v\x0f\xb9\xd1\xd3\xd02\xecQ\x9a\xd7aL\xdf\xc1~u\xca\x8a\xd4xk\xde\x030;\xb2Q\xc8$\xddQ\xd3Jj\xd1U\xccV\xd1\x03\xa9\xbf\x9f\xed\xe68n\xac&\xd67\x0c\xfd\xc6^\x0e\xb40\x07\x97|\xab\xadBc<T\x0b d$\x94\xf9\x90Oq\x027\xe4\xf2\xec\xc9\xbc\xfaL7dN\x83\x96X\xab\xf7\x18\xad\xfc\xf7\x992\x87\x1d\xe8p\x97C\xd4D.\x1b;F_ \x91t\tM\x155\x0c\xb9\x9f\xd0W C\x19oz4.\x998\xe7\xa9\x98\xd4\xd2\x9f\x95H\x91\xf2`\x1c\xfa\xa4,\xa9d?day\xc4\xf3\xcb\xc8r\xf7\x97\xd1u\xfe\xec\x91\xc1\xe6V\xa3j\x0f\xb9\xd5\xa1a\xd5\x17\x8b!\xc4{A\xb2t\x85\xfe\x88\xffaO\x05\xc5\xacg\xed;]\xb9\xdd\x7fS\xef\xe4F\xf9"\x0c\xd9\x1a\xb6\x88-Y \xdd\xea\xc9\xf1>:\xbf][\xdf[\x07\xb9\xe2@\xeeq\xf9Ho\xc3\xc4sD\xcd\xcc\x8a\x11tq\xf6;\xe9\x84\x7fb\xe9\xf4t\x80\xe4l)_\xeaQ\x10\x8f^-\xc5\x11\xe7\x84x\xe7-\xb2\x15[5\xb0\xdck\x1awh\r;\x9by\x14\x1a\xe0:\xbd\x904\xa2\xfap[\xe0\x9fn3\x7fk;3n\xf8\xe3%\xc6t\xbf|\x12\x9a\x1b\xe2\xf1C\x10\xbe\xee\xe7.\x98>k\xb9r\xf9\x9cN8\xae\xc0\x8bA\x0f\xbb\x8d\xf4\x04\xb0\x01,\x05\xaa\xc5\r\xce\x91\'\x98\xc6\xd3Y\x1b\xd1U\xd3\xd7d|{I\x18JG\xa63\xd6\'r\xcf!7\x17qd\xb7|\x1f\x7f\x17\xb4\xa8\xb9\xa8\xdaz\x02g\xc7+]F\x10\x18l\x0c\x91g\xd0e\x1f\xe4\xa67\xb2\xba\x9f\xef\xba\xc7[3_\x12C\xe9\xf4s\x87q\xa3\xec\xa0\xcc\x06\xf4\x9f\xe1\xb3\xe6R\x93\xf2\xd57i\xf8\x96\xb3x\xa7uEw\x12D\x8c\xc6XkdfY\xe0J2N\xbf\x85o\x8e\x81|C\xa91#y\xd9u\xf1\xd1BC\xcc}\xe8;?\x12S\x16', 2)

PyArmor…

If you’re not familiar with PyArmor, it basically here to drive you crazy. It obfuscates the bytecode, the strings, it verifies the integrity of the script, it’s a real nightmare. So, because it was not possible to modify the program, and it was a pain to debug, we decided to dig into the Python source code itself.

A nice approach was to find the place where Python evaluates the code. An interesting function was _PyEval_EvalFrameDefault in cpython-3.7.9\Python\cevel.c, and especially its argument PyFrameObject *f.

PyFrameObject is a _frame structure declared in cpython-3.7.9\Include\frameobject.h:

typedef struct _frame {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

struct _frame *f_back; /* previous frame, or NULL */

PyCodeObject *f_code; /* code segment */

PyObject *f_builtins; /* builtin symbol table (PyDictObject) */

PyObject *f_globals; /* global symbol table (PyDictObject) */

PyObject *f_locals; /* local symbol table (any mapping) */

PyObject **f_valuestack; /* points after the last local */

/* Next free slot in f_valuestack. Frame creation sets to f_valuestack.

Frame evaluation usually NULLs it, but a frame that yields sets it

to the current stack top. */

PyObject **f_stacktop;

PyObject *f_trace; /* Trace function */

char f_trace_lines; /* Emit per-line trace events? */

char f_trace_opcodes; /* Emit per-opcode trace events? */

/* Borrowed reference to a generator, or NULL */

PyObject *f_gen;

int f_lasti; /* Last instruction if called */

/* Call PyFrame_GetLineNumber() instead of reading this field

directly. As of 2.3 f_lineno is only valid when tracing is

active (i.e. when f_trace is set). At other times we use

PyCode_Addr2Line to calculate the line from the current

bytecode index. */

int f_lineno; /* Current line number */

int f_iblock; /* index in f_blockstack */

char f_executing; /* whether the frame is still executing */

PyTryBlock f_blockstack[CO_MAXBLOCKS]; /* for try and loop blocks */

PyObject *f_localsplus[1]; /* locals+stack, dynamically sized */

} PyFrameObject;

And what’s even more interesting is that it contains PyCodeObject *f_code declared in cpython-3.7.9\Include\code.h:

/* Bytecode object */

typedef struct {

PyObject_HEAD

int co_argcount; /* #arguments, except *args */

int co_kwonlyargcount; /* #keyword only arguments */

int co_nlocals; /* #local variables */

int co_stacksize; /* #entries needed for evaluation stack */

int co_flags; /* CO_..., see below */

int co_firstlineno; /* first source line number */

PyObject *co_code; /* instruction opcodes */

PyObject *co_consts; /* list (constants used) */

PyObject *co_names; /* list of strings (names used) */

PyObject *co_varnames; /* tuple of strings (local variable names) */

PyObject *co_freevars; /* tuple of strings (free variable names) */

PyObject *co_cellvars; /* tuple of strings (cell variable names) */

/* The rest aren't used in either hash or comparisons, except for co_name,

used in both. This is done to preserve the name and line number

for tracebacks and debuggers; otherwise, constant de-duplication

would collapse identical functions/lambdas defined on different lines.

*/

Py_ssize_t *co_cell2arg; /* Maps cell vars which are arguments. */

PyObject *co_filename; /* unicode (where it was loaded from) */

PyObject *co_name; /* unicode (name, for reference) */

PyObject *co_lnotab; /* string (encoding addr<->lineno mapping) See

Objects/lnotab_notes.txt for details. */

void *co_zombieframe; /* for optimization only (see frameobject.c) */

PyObject *co_weakreflist; /* to support weakrefs to code objects */

/* Scratch space for extra data relating to the code object.

Type is a void* to keep the format private in codeobject.c to force

people to go through the proper APIs. */

void *co_extra;

} PyCodeObject;

It was everything we were looking for: a file name, local variables, opcodes, etc… So we modified _PyEval_EvalFrameDefault in order to dump the frames passing by and recompiled Python:

_PyEval_EvalFrameDefault(PyFrameObject *f, int throwflag)

{

FILE* dump = fopen("/tmp/python.dump", "wb");

PyMarshal_WriteObjectToFile(f->f_code, dump, 2);

fclose(dump);

...

}

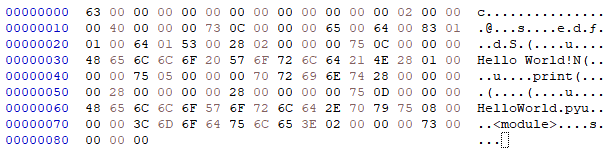

As we tried it on a simple python program, it was working great:

#HelloWorld.py

print('Hello World!')

Once executed with our modified Python, the content of python.dump was:

>>> import marshal, dis

>>> dis.dis(marshal.load(open('python.dump', 'rb')))

2 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (print)

2 LOAD_CONST 0 ('Hello World!')

4 CALL_FUNCTION 1

6 POP_TOP

8 LOAD_CONST 1 (None)

10 RETURN_VALUE

But it was too good to be true… 11.py was far more complex, and because of all the references and different objects, we couldn’t get the whole code at the level…

Then, we noticed an intriguing piece of code in _PyEval_EvalFrameDefault:

call_trace_protected(tstate->c_tracefunc, tstate->c_traceobj, tstate, f, PyTrace_CALL, Py_None)

So we thought about the trace Python module, was it possible to trace 11.py even with its protections? Well… guess what?

But how does it work??

Let’s take a look at cpython-3.7.9\Lib\trace.py:

...

try:

with open(opts.filename) as fp:

code = compile(fp.read(), opts.filename, 'exec')

# try to emulate __main__ namespace as much as possible

globs = {

'__file__': opts.filename,

'__name__': '__main__',

'__package__': None,

'__cached__': None,

}

t.runctx(code, globs, globs)

except OSError as err:

sys.exit("Cannot run file %r because: %s" % (sys.argv[0], err))

except SystemExit:

pass

...

...

def runctx(self, cmd, globals=None, locals=None):

if globals is None: globals = {}

if locals is None: locals = {}

if not self.donothing:

threading.settrace(self.globaltrace)

sys.settrace(self.globaltrace)

try:

exec(cmd, globals, locals)

finally:

if not self.donothing:

sys.settrace(None)

threading.settrace(None)

...

In fact, trace tries to emulate the __main__ namespace so programs can’t catch it! It compiles the program, and executes it with the emulated namespace. So we reimplemented it in order to get every single frame and read them.

And here comes Py Frame Trace, a basic tool made to read the frames you want from a program by applying the right filters!

If we wanted to filter the right frames, we had to have an idea of what 11.py did.

I know what you’re thinking… But

The good news is that we knew that the python script sends a request over the internet and base64 encode something. So we tried to look for those frames.

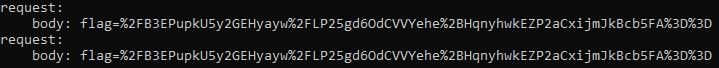

First, we wanted the body of the request, python3.7 pyframetrace.py 11.py --name request --lname body:

Then, we looked for a b64encode, python3.7 pyframetrace.py 11.py --name b64encode:

This is not very human friendly… So we checked the different functions called by the program, python3.7 -m trace -l 11.py:

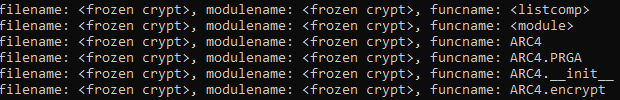

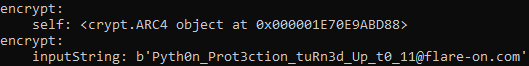

So we filtered python3.7 pyframetrace.py 11.py --name encrypt:

Little bonus, there was the RC4 key in the __init__, python3.7 pyframetrace.py 11.py --name __init__ --lname key